This week we caught up with artist and friend Tunji Adeniyi-Jones. Tunji is currently doing his MFA in Painting at the Yale School of Art.

Skin Deep: Your work seems to reflect influences of the ancient past, the recent past, the present and the future – there is an interesting sense of its position in terms of time and location.

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones: That’s a great observation. I am always considering my position both culturally and historically. I’m really excited by the prospect of establishing timelines for my work to move around in. Observing the relationship between the masks that I first made and my more recent pieces is a fun exercise.

This then becomes more complex when you consider how all West African masks have, for the most part, been exhibited anachronistically. So now I’m considering the importance of letting the audience know whether one object was made before the other.

SD: More generally, being part of the multimedia generation who can constantly access stimulation, what kinds of things/people/sounds/styles influence your work?

TAJ: At the moment I can’t work effectively without some sort of music playing in the background, so that’s the most immediate stimulation I receive on a daily basis. I also spend a lot of time digesting images and information on my phone and laptop. I try to be as productive with this as possible, but hours are definitely overspent on social network platforms.

Everything else is a combination of experiences I’ve had in the past. I grew up in a house full of traditional West African sculptures, paintings, prints, and textiles. Being around those objects at such a crucial time of my development has undoubtedly affected my current taste and preferences.

SD: In the past you have created intricate collages involving masks, landscapes, militants; in recent work you seem to have extended this use of collage to more sculptural fabric pieces – what draws you to collage as a medium? Is there perhaps an attempt to portray a fractured reality or maybe more optimistically a multiplicity of influences that are not contiguous?

TAJ: The collage was a tool that I used to express my relationship with my Nigerian background. It was a process of discovery and understanding. Now that I’m more comfortable in my skin, I’m less reliant on the collage as the primary medium to express myself. It may well come back into my work in the future, but right now I’m trying to push my painting and printmaking.

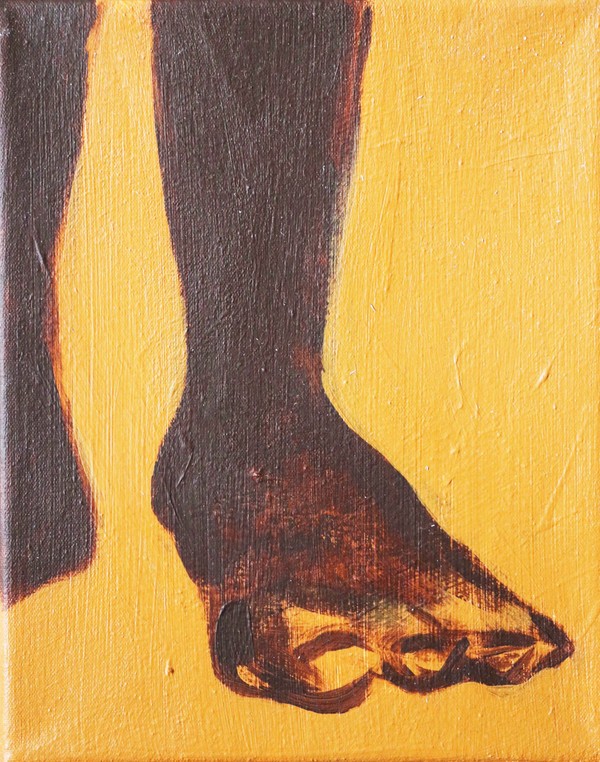

SD: Masks are a common presence in your work – why use masks and on black bodies? The way in which these are depicted is definitely modern – how do you draw the line between your art becoming a caricature vs a new imagining?

TAJ: Initially I used the masks as part of a performative exercise, and I felt it necessary to use myself as the subject. It wasn’t so much a conversation about being black or white as it was about being British or Nigerian. I feel that this is an important distinction to make. Although these two propositions are similar in nature, my intention was for the work to be more specific than just a mask on a body. The fabrics used in the masks have a very specific and diverse history. In my most recent work the masks stand autonomous as individual characters, free from a bearer. I feel that this liberation and subsequent focus on the mask itself as a historical object will push the work away from caricature.

SD: Our next issue is focused around the theme ‘Imagining 2043.’ How do you see the world of art makers/creators in 2043? What will artwork/creative pieces look like in 2043?

TAJ: I think we will experience fewer things materially and everything will be consumed digitally. By then I’m sure you won’t even have to go to a gallery, you’ll be able to pay for an online virtual tour bundled in with your Netflix account. It will be an interesting time for painting. The value of original handmade craft could either rocket or plummet. Either way, it’ll be an exciting time to be an artist.

Check out Tunji’s website here

Skin Deep Meets Tunji Adeniyi-Jones