As a British Nigerian, studying in the US has been a nomadic experience. I’ve gotten used to packing up my life every ten weeks and living out of suitcases. I spend major holidays with friends’ families and carve out spaces to call home in cities that aren’t my own. As a child of the African diaspora, I already experience a psychic and sometimes geographical sense of rootlessness, but this occidental diasporic existence sheds light on another dimension of intangibility: as I move, my blackness, too, shifts. Switching one permutation of white hegemony for another, my race can become a marker I do not personally embody and cannot quite grasp.

I was home in London for a few weeks in December, and decided to sort through the last remaining bits of me in my childhood bedroom. Digging deep into the back of my wardrobe I found the fitted black sequin floor length gown I wore to my sixth form prom. As I held it up I thought back to that night and my time at the school. I thought back to the initial shock of moving from a state school ten minutes from my house to this private one halfway across London; to the shock of being completely surrounded by white people having spent my life existing amongst shades of black and brown. Over time, my new school became a space where I could embrace the parts of myself I had previously suppressed. It is where I learned I wasn’t always going to be the smartest person in the room (those early essay comments still keep me humble). I learned to push my limits and not always expect rewards. I learned mediocrity is enough for some people to succeed, and that those people would hardly ever look like me.

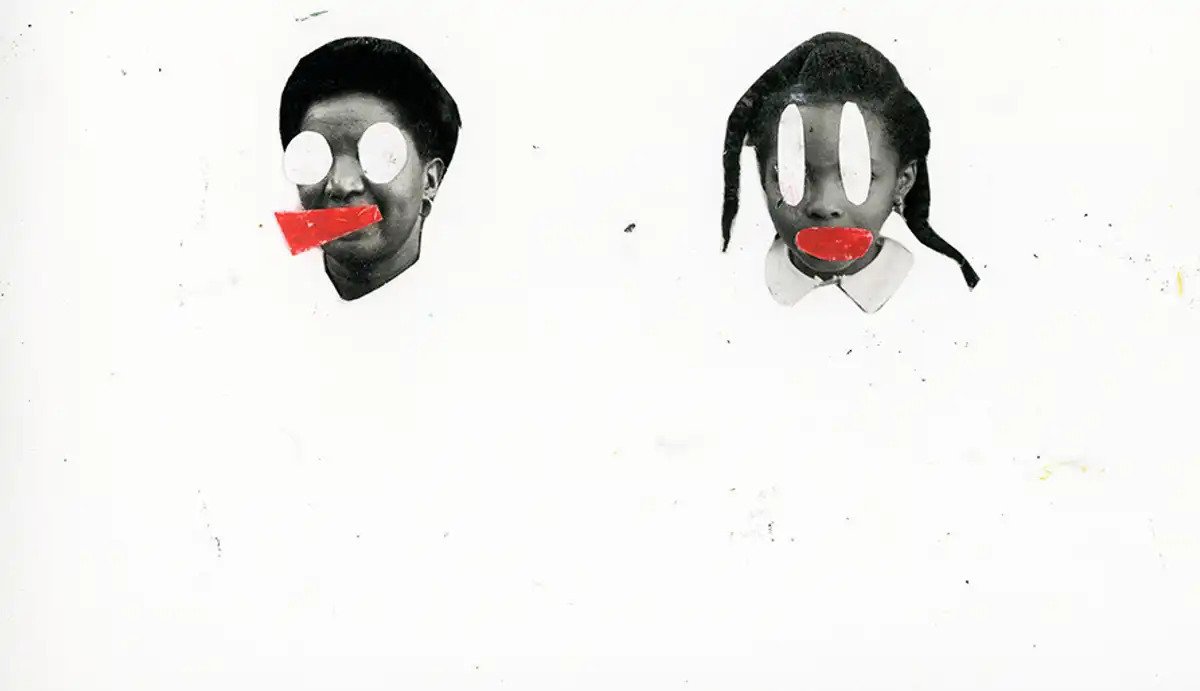

Mine was an independent school in one of those suburbia-in-the-city enclaves of West London, where rich people who never call themselves rich live. My school friends were lovely and, for the most part, inclusive. Some would make jokes followed by “it’s not racist, just racial”, or occasionally address me with an exaggerated ‘urban’ vernacular born in a London clearly foreign to them. But it all felt very benign, the gentle teasing, the marveling at my hair, the way my accent gradually changed. To be black at my school was to be one in an eighty-strong sea of white, to notice it but not dwell on it. It was to be invited to the parties, to have great dress sense and great ever-changing hair. It was to have a lot of friends, but end up closest to the mixed raced girl. It was to witness racial stereotyping but never really interrogate it because you were not the stereotype. It was to wish you could find the words to describe your experience, but have no one around in a position to give them to you, or even recognize they should exist. My blackness, in its proximity to whiteness, was simultaneously exalted and ignored. It became performance, exemplary, definitive, something that was more than just my own.

I constantly felt like I was proving points: proving that I could be black and take a joke, that I could be black and take some of the hardest subjects, that I could be black and still get some of the best grades. I knew I had an audience even if they – ‘colourblind’ – didn’t recognise that’s what they were. I existed in perpetual proximity to their disembodied stereotypes: hoodrat, weave wearer, angry, occasionally becoming each and none of them (because I’m a complex human being.) Still, inherent to my experience was a constant pushback against essentialized understandings of my race, against deeply ingrained prejudices and modes of thinking that always felt too normal to call racist. Flawed or not, I wanted to be the version of myself that proved blackness didn’t equal limitations.

My predominantly white institution in the US has been no different in many respects, but being here has forced me to take a deeper search for those words I could never find whilst in sixth form. As a British Nigerian I inherit a colonial legacy; I am a descendant of the wrong side of the empire, who only knows the right side as home. The racism I ingested growing up is born from a defiant social, political and, up till recently, cultural ignorance of this fact. When my surrogate nation denies the truth of my disrupted history, refuses to recognise the determination, strength and power that underpins my very existence, it is easy to see why being surrounded by white people means being surrounded by muted expectations. When the mayor of London, an Oxford-educated member of the upper class, says British colonialism made manufactured nations like Nigeria more ‘fortunate,’ it’s easy to see why people believe my success is driven by luck and white altruism. I can be angry and I can be offended, but I cannot be surprised, for this is how my society was structured to be.

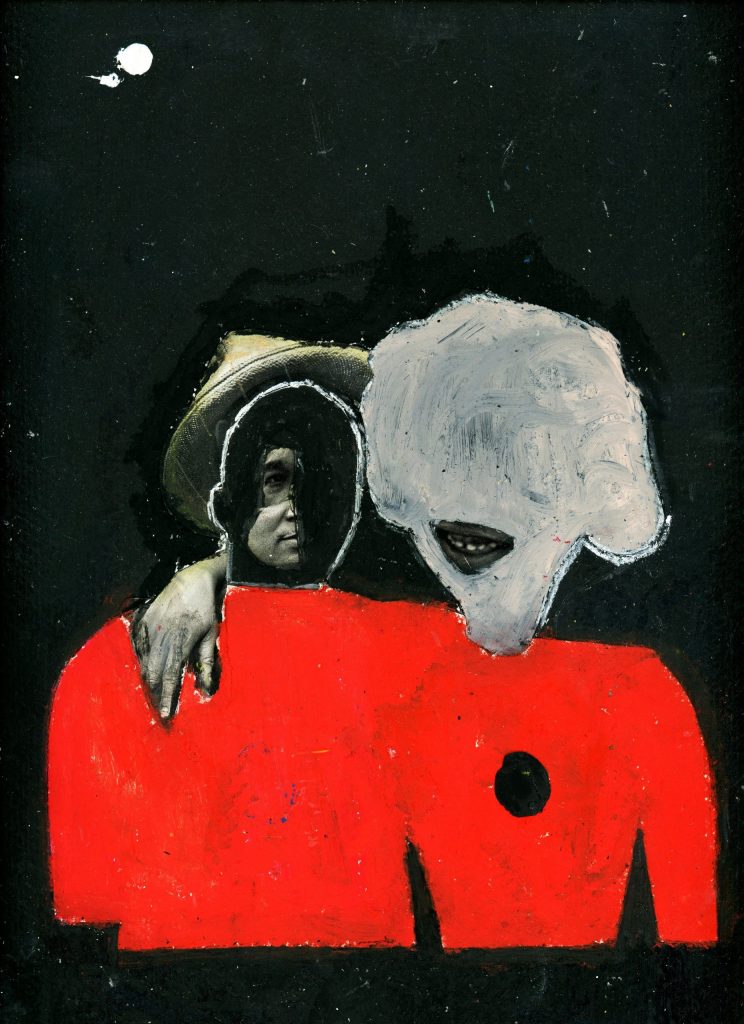

Yet now my blackness, displaced from the city in which it was born, is forced into a new set of foreign labels and legacies. Being black in the US means experiencing a similar yet unique brand of racism, where an entire race can simultaneously build and be subjugated by a nation. It’s a racism where said race can then be blamed for that subjugation and be labelled racist for pointing out the distressing irony. By this logic, black men are incarcerated for drug crimes at disproportionate rates because they are disproportionately criminal, not because colourblind drug laws allow similar drugs to be punishable at wildly different levels. That their white counterparts use the exact same drugs at similar, sometimes higher, rates is of no importance for this logic. Similarly, race-based wealth inequality exists because black people haven’t quite figured out how to pull up those bootstraps and work hard. It has nothing to do with the fact that, even post-Emancipation and Jim Crow, blacks have systematically been excluded from various wealth-building government policies, policies that white people still benefit from today. And it is of no consequence that my resume could be identical to a white man’s, but my black sounding name gives me a much smaller chance of being hired. Like British colonial anti-blackness, it is dynamic, constantly shifting with the reigning social order, finding new ways to keep black people in a perpetual state of not-quite enough, of not-quite free.

I’ve often felt like an anthropologist, part of but slightly removed from the way things work here. I get angry more often, I’ve had to learn what self-care really means, I take days where I don’t read anything in the news. I’m learning to identify and avoid the white liberals who see me as a safe choice, a different kind of black who can be impartial, who also believes the devil needs an advocate, because my lack of African-Americanness somehow makes me closer to white. These people seek me out for discussions on why really ‘all lives matter’, on the real issue of black on black crime, on Miley for goodness sake! For them my blackness is enlightened; I am black but British. My humour, my style, my cultural references and my accent, all these things built elsewhere that are mine become markers for them, markers of a quasi-blackness, a manufactured race that just isn’t my own. I’m learning, that “blackness in the white imagination has nothing to do with black people.” But mostly I’m learning to exist in this space, knowing the difference between what I am and what I must take on, and knowing that difference is not enough to save me. After all, my Britishness won’t stop a bullet.

States of Black