We cannot talk about the future of black feminism without talking about white feminist pasts. I have been a feminist for some 40 years, ever since I came to Britain in the 1970s as a young women from Trinidad. This was a heightened time for black social movements and feminist activism, but despite all that I had never heard of Indian women Suffragettes until a few years ago when I stumbled upon a crumpled photograph in a dark corner of a museum. Suddenly like a ray of light, I saw myself in history! I discovered a hidden genealogy of feminist women of colour in the West! Yet in contrast to the activism of white British Suffragettes, these Indian women were described as no more than exotic multicultural creatures in colourful saris. Gayatri Spivak, the postcolonial critic, calls this erasure and reconstruction of colonial history an ‘epistemic violence’ in which white women are seen as the only legitimate agents of struggle and ‘third world’ women are dark, mute, visible objects.

But let us fast forward now to 2015, when the film Suffragettes was released to mark their centenary. At the film’s launch the female cast, headed by actor Meryl Streep, wore shirts emblazoned with Emily Pankhurst’s famous quote, “I’d rather be a rebel than a slave.” This thoughtless, racist publicity stunt was an insult to the descendants of the enslaved who did not ‘choose’ to be a slave and whose fight for freedom was not supported by many Suffragettes. For them, rebellion was to be ‘human’ and stay alive. This suffragette story shows us how feminism is fraught with intersectional tensions. Whose voice, whose platform do we hear? How is women’s ‘difference’ recognized and acknowledged? There is a strong thread of colonialism that runs through mainstream feminism – or should I say ‘white’ feminism? In the 21st century we still have to ask, ‘if feminism is now anti-racist, intersectional and inclusive then why do we still need ‘black’ feminism?’ Maybe because it is not!?

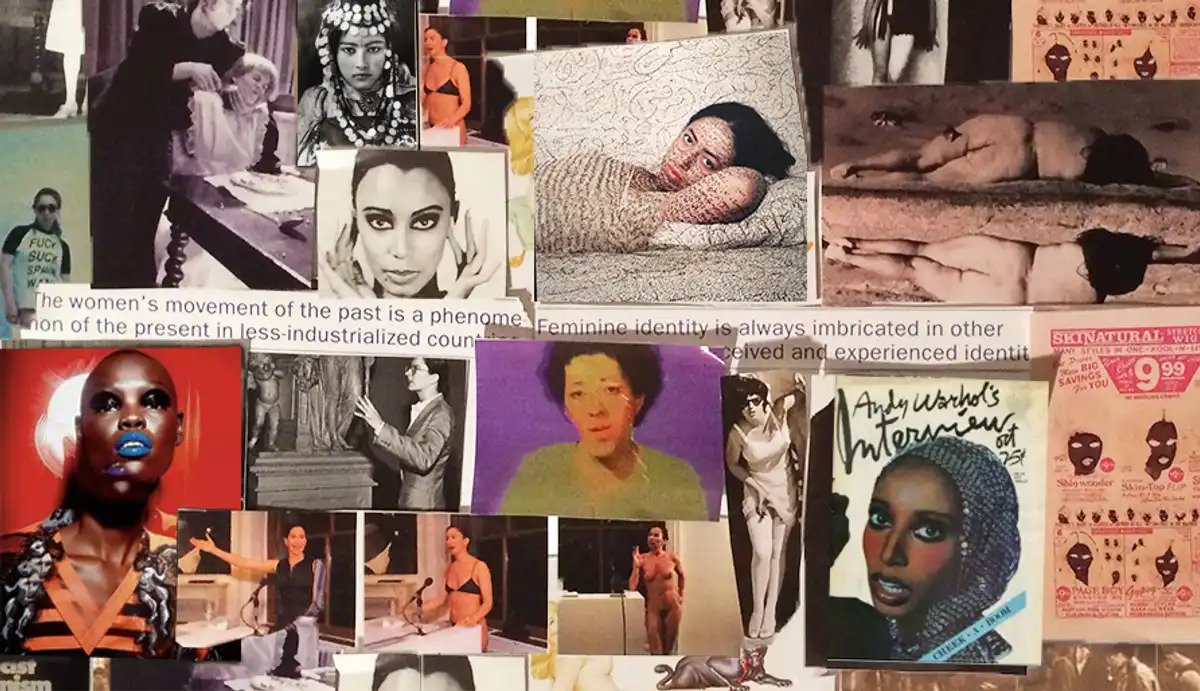

Intersectionality is at the heart of black and postcolonial feminist theory. Cut us open and you will see our multiple identities where race, gender, class, sexuality, religion, nationality, age, and disability bleed into one woman’s life. As a young black woman recently told me, ‘Intersectionality runs through all of us’. Intersectionality enables us to reveal, from the standpoint of our embodied lived lives, how oppressive systems of power work through our sexist, racist, classist institutional structures. For example: the racialised state surveillance of Muslim women who wear the veil, and are subject to state-sanctioned anti-terrorist measures that violate their human rights. Similarly, the #SayHerName vigil for Sarah Reed, who was beaten by the police and later died in a British prison, highlights the systematic state-sanctioned violence against women of colour.

However, while intersectionality is a ‘lifeline’ for black and postcolonial feminists of colour, it has become a ‘buzzword’ for white feminists: a political concept devoid of any real meaning. To claim an anti-racist position by simply declaring, ‘we are inclusive…..we are having an intersectional event’, you ‘tick the box’ of intersectional doing, but it does not fundamentally challenge your underlying thinking. Recently at a mainstream white women’s political meeting they declared that they were an intersectional party. They regaled us with middle-class feminist concerns about equal pay, women in the board room, and childcare. A young black woman party activist asked what the party may offer her mother – an older, retired, migrant black African woman. An embarrassing silence followed, finally we were told they had made a special trip to a tough urban ‘ethnic’ area. The black women who came to their meeting did not respond well to this; they were so angry the white female politicians cried and ran out of the room! Black women get angry about being excluded and their issues not being addressed, but when that anger is expressed it unintentionally reinforces the white expectation that they are ‘angry and difficult’, which in turn justifies their exclusion as they are seen to bring ‘bad feelings’ into the room, making white women feel guilty!

The white women activists in the meeting, however, did not feel ‘guilty or bad’ about championing the campaign against FGM (female genital mutilation) and honour killings. The ‘saving’ of oppressed Muslim women from barbaric patriarchal customs ‘out there’ in far off places, is ‘safe ground’. This reaches back to the colonial idea of the superiority of white Western civilization. In the zeal of these missionary acts of ‘saving others’ we forget to look at the poverty, mental health, destitution, and sexual violence that women are subjected to right here on our doorstep in Europe.

As we go forward in the 21st century, we need to think about what feminist solidarity really looks like and how to be better allies to women who are ‘not like you’. The enemy – patriarchy – is greater than the sum of our black and white feminist parts. We need to keep our ‘eyes on the prize’ and build a truly universal, inclusive feminism that keeps in its sights how patriarchy cleverly ‘hides in plain sight’ behind the neoliberal illusion of greater gender and race equality. This new terrain of struggle is very different from 100 years ago, when the suffragettes and postcolonial people of colour were physically excluded from centres of white male power. We need new strategies for new times and I am heartened by a generation of hopeful, confident black feminists whose strident cyber critiques of neoliberalism aim to expose the continuing inequalities of race, class and gender in all their manifestations. The black feminist movement is vibrant, the black feminist movement is global!

Black Feminist Futures: White Feminist Pasts