Les Blancs opens with a woman, impossibly tall, her breasts and legs daubed with blood, walking slowly across the smoke-filled stage. She confronts the audience with a haunting mixture of pain, strength and defiance, setting the tone for this production of Lorraine Hansberry’s last work.

Set in a fictitious Central African country, Les Blancs tells the story of the dying days of Western colonialism. The dusty wooden structure onstage throughout is the hospital run by Madame Neilson and her husband, missionaries who have lived in the village for 40 years. The play follows the arrival of a spunky American journalist, Charlie Morris, who has come to document the Neilsons’ devotion to the natives, only to discover that tensions are at an all time high. ‘Terrorists’ have been attacking settler families, hacking them to death in their sleep in a violent bid for independence. After centuries of brutal colonialism and the failure of diplomacy and petitions, the villagers have taken up arms – with two exceptions: Abioseh, who has converted to Christianity, and his younger brother, Tshembe, newly returned from travelling in Europe and America.

Tshembe’s dilemma is a painful one. Back in London he has a family to whom he longs to return, and yet he is loath to abandon his country in its time of need. In his conversations with Charlie, Tshembe airs his frustration that as an educated black man he is expected to have the answers. He despises Charlie’s assumption that violent protest is always wrong, and yet cannot pick up the machete himself. After a humiliating interaction with the sadistic Major Rice, Tshembe is further disrespected by Charlie as he assures him, “I knew what you were feeling back there”. Charlie is the arrogant white ally, convinced that he can make a difference, who comes to realise the extent to which history has been whitewashed through the course of the play. The poverty of the mission is designed to keep the villagers dependent on the benevolence of the Reverend and his wife. No matter how good their intentions, those who work at the hospital are participating as fully in the racism of the colonial project as the trigger-happy Major.

Danny Sapani gives an impressively controlled performance as Tshembe, vacillating between anger and vulnerability. James Fleet also stands out as the disillusioned doctor, his passivity as damning as it is intriguing. The sympathies of the audience are continually shifted, and in this respect the play is highly sophisticated. However, the strength with which the message of the play is reinforced leaves little room for the audience to tease out implications or engage more analytically with the material. One senses that the playwright, Lorraine Hansberry, was unwilling to take any chances; she wrote the play in 1965 when many African countries were still yet to gain their independence.

Hansberry, who inspired Nina Simone’s To Be Young, Gifted and Black, blazed a trail as the first African-American woman to write for Broadway with her 1957 play, A Raisin in the Sun. It centred on racial segregation in Chicago, an issue close to her heart: her own family’s case to contest the restriction that banned African-Americans from purchasing land in a White area was heard in the Supreme Court. Tragically, Hansberry contracted pancreatic cancer and died at the age of just 34.

Yaël Farber’s production for the National Theatre is a welcome revival of Hansberry’s final play, posthumously compiled from drafts by her husband, Robert Nemiroff. Farber delivers a new version of the text, with updates from Drew Lichtenberg and Joi Gresham of the Lorraine Hansberry Literary Trust. The starlit backdrop, designed by Tim Lutkin, and the ominous, rumbling soundscape from Adam Cork compound the text’s atmospheric mixture of amazement and terror. Les Blancs is a testament to the charisma of Hansberry’s theatrical voice; it is a captivating and disturbing enactment of the horrors of Western imperialism.

Get tickets to see Les Blancs here.

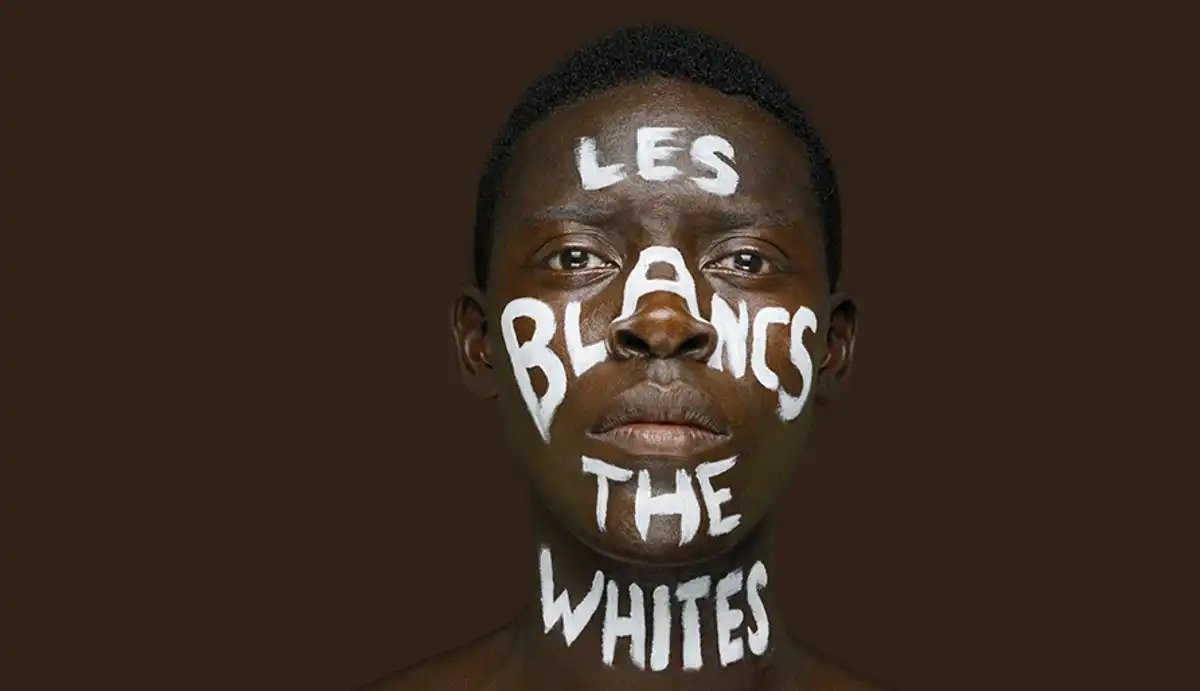

Review: Les Blancs by Lorraine Hansberry at the National Theatre