Mona Chalabi is the Data Editor at Guardian US, and a journalist who really loves numbers. She uses statistics to look into current issues, social just issues and random facts that you might be interested to know. We sat down with her to find out why statistics matter, what they have to do with justice and what it means for her, as a woman of colour, to present information through data. Here’s our interview:

*

Skin Deep: What drew you to statistics?

Mona Chalabi: I don’t remember this at all, but I found this “about me” that I had written when I was seven, and it says in there that I liked maths. So I actually always quite enjoyed maths when I was younger. I started hating it when I was a little bit older, as most people do. When I graduated, it was such a tough job market that the only job I could get was one doing monitoring and evaluation in a humanitarian organization, which was kind of linked to the international security stuff that I’d studied at school. But my specific role within that organization was whatever the hell I could get, you know. It was nothing to do with my skill set.

SD: There are a lot of great cartoons (some of which you draw yourself), graphics and videos that accompany the articles and the ‘Just the Facts’ segments you write. Do you think the way in which statisticians present data is important and what are you trying to do with the quirky visuals that you use to present information?

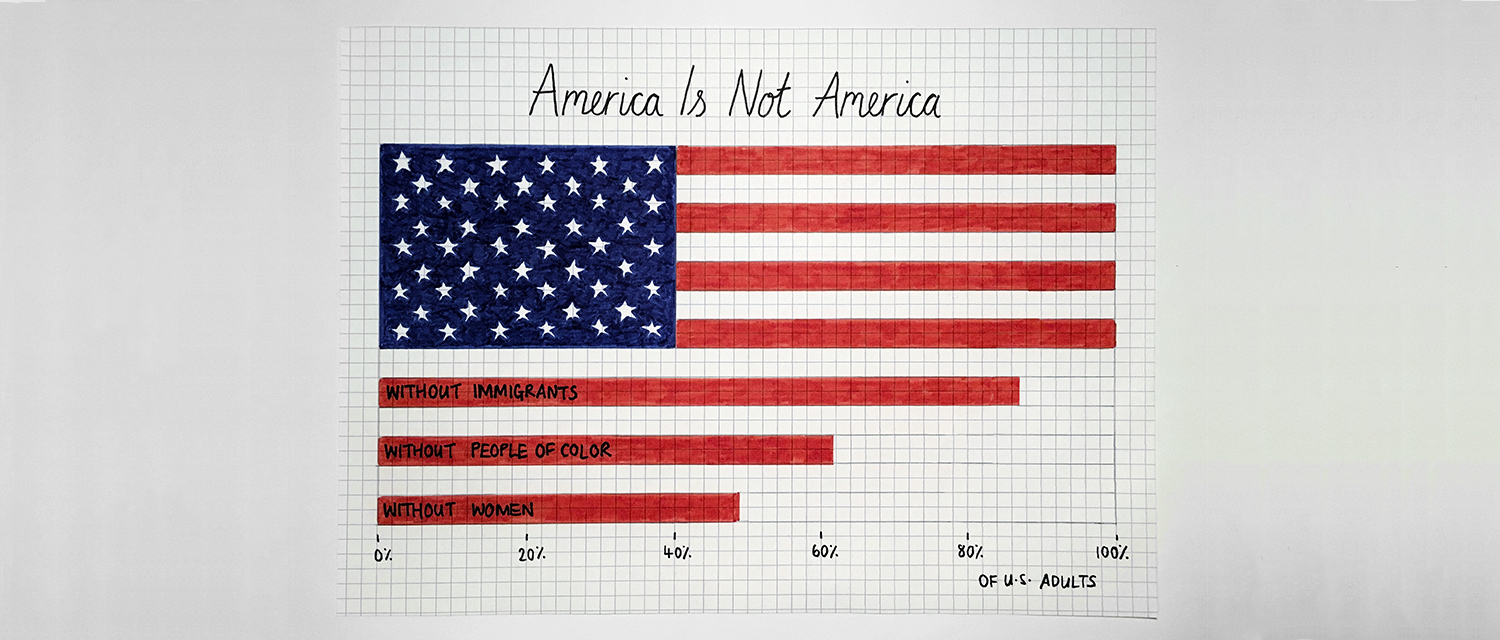

MC: I think it’s really important. Very often they [statisticians] are producing visuals for each other, as opposed to a broader audience. My goal, as a journalist, is to get people who aren’t part of the stats community really interested in the numbers, especially the people who are most affected by them. So, if I’m doing a chart on the immigration ban, I want people who are potentially affected by the immigration ban to be able to see it and make sense of it very quickly – people who aren’t necessarily going to dig into an 800 or 1000 word piece. That’s the audience that I’m targeting.

And with the illustrations, there are opportunities to show people your workings. I’m constantly trying to think about ways to bring them in. The way that I am doing that most commonly, at the moment, is through my Instagram stories. I’ll post the finished sketch on my main Instagram account, but you can look up my story from that day and see me scrolling through the spreadsheet that I used to find the numbers, me producing a kind of classical chart to figure out the shape of those numbers, me sketching it… It just makes people feel a little bit less like it’s just some kind of weird magic.

SD: Most of us are, to a large degree, statistically illiterate. In the sense that we can understand what the numbers are saying when they are put in front of us and accompanied by a narrative to tell us how these numbers are operating, but we’re incapable of scrutinizing the methodologies and approaches that were used to render a particular data set or result. How does your work attempt to bridge that gap?

MC: I try to show people the process, just like when you were a kid and you were always told to show your workings. Rather than give readers an ultimatum, saying “Either you believe the statistic that I’m giving you or you don’t”, you try to walk people through how you got there. I try to do that as much as I can with my writing by saying things like: “You know, I went to this source. I trust this source because of these reasons…”

Rather than just look at the number of crimes committed in a particular city, what I do is divide the total number of crimes committed by the total population so that I get an adjusted rate. Otherwise, you’re just going to get a data set that says that there are more murders in bigger cities… Talking people through how you do all these different calculations empowers them to ask the same set of questions when they’re looking at other statistics. They’ll learn to ask questions like: has this been adjusted for the population size? Has this been adjusted for age, for gender, for all these different things?

SD: So, do statistics lie?

MC: Yeah, I mean, people lie. And people use statistics [to lie]. It’s kind of just as simple as that. There are so many ways in which I can manipulate the statistics to tell whichever story I want. I just try to be super conscious about the way that I am doing [the work], so that I’m honest about that. I think one thing that we probably have to get better at is just publishing the dataset itself, as well as the final analysis, which is something that we used to do but has gotten a little bit time-consuming. But publishing the data set means that if I am saying to you: “You know, this is the way that this thing has changed,” you could actually be empowered to say “Oh, you’re only really showing the way that it has changed since 2000, but the entire data set goes back to 1960 and if you take that into consideration it looks totally different.”

SD: You seem to use statistics as a way to challenge beliefs that are widely held, particularly on issues like crime, immigration, terrorism, and jobs. Could you speak a little bit as to why you use statistics to look at these issues and what work you think they are doing, in terms of revealing something about our beliefs around these issues that rhetoric is not able to do?

MC: I use statistics partly because I think they generate a different kind of debate. Rather than people saying to me “Well, of course you think that, you’re a woman, or you’re not white or blah blah…”[Using statistics] means that people can say things like “Well, is that a reliable source? Are there other reliable sources?” The nature of the conversation feels less intractable because you can say “Well, actually, there is this other source and it says this”, which allows for more of a dialogue.

I do think that [statistics] can be more powerful than rhetoric. For example, an illustration I am working on this week is on the new travel ban. The rhetoric around that is that these countries pose a threat to US national security, but the statistics and data directly contradict that. You can pull up data that shows how many nationals from these countries have killed US citizens. You know, the data I’m looking at is from 1975 – 2015, [which amounts to] forty years worth of data. If there have been zero murders by nationals from these countries [on US soil], and you are still saying that this is a national security issue then…Hopefully, [the statistics] are doing something that challenges the rhetoric a bit.

SD: Given how statistics have been historically used by demographers, the state and politicians to police certain populations and particularly communities of colour, what does it mean for you, as a woman of colour, to be using the same “tool”, as it were, to undo some of the structures and policies that have been legitimized through the use of the “science” of statistics?

MC: I think I might disagree slightly. It’s absolutely true that they have been used to police those communities, but they have also been used to inform policy. And, yes, in societies that are incredibly racist, part of that policy is about subjugation. And, yet, the idea of using air quotes for the ‘”science’ of statistics” is super frightening to me. They [statistics] were honestly about understanding the size of the population and what that population needed. That was ultimately the goal at the very start of statistics, and statistics are called statistics because they come from the state; the state is really the only organization that is best in power to collect those numbers –not a private company.

Numbers are very important for justice. That’s what I’m concerned about under the Trump administration, which is that people hold exactly your view. [For example], there is a Bill in Congress [right now] that I’ve written about before, which is saying that federal money can’t be used to measure racial segregation in cities. The existence of those numbers is actually preventing racial injustice. Not collecting them means that it is going to be [the word of] communities of color, who are saying we’re living in these ghettos, pitted against the state, which can then respond by saying, “Well, you claim you are, but there is no evidence of that, because we don’t have numbers.” So, my personal belief is that, actually, statistics are absolutely integral to activists and anyone who is trying to pursue a cause. I know that’s not what human rights are about, I know you don’t need to claim that this many people are being affected by something in order to be moved to action. However, discrimination is about systematic patterns of behavior, and proving those systematic patterns requires data.

SD: I agree with you, but I think historically, because of how data and the census were used by colonial governments to police, regulate and divide the native population, people learned to become wary of the census and data in general. Which is why it’s interesting to see you reclaiming the tool and repurposing it.

MC: I kind of feel like it’s really difficult because the skepticism isn’t a bad thing. I can understand the skepticism. It’s about it being channeled in the wrong direction. For example, with polling, particularly the sort of polling that was used in the lead up to the US election, I know that non-whites are less likely to answer questions, and I include my family in this. They are inherently skeptical and frightened of power and they’re wondering “Who is this person at the other end of my [phone] line who is saying they just want to collect the numbers out of curiosity or whatever, who is asking me how I intend to vote? No way…” So, their views aren’t being captured, which makes the numbers incredibly misleading. Now, the consequences of that are incredibly vague. It might be that the polls overestimated Hillary Clinton and as a result of them overestimating Hillary Clinton fewer people turned up to vote for her because they felt surer of a win. Or, it could be that because the polls overestimated Hillary Clinton, people thought that Donald Trump was this poor underdog and showed up in greater numbers [to vote for him]. Who knows exactly how that worked? But, you know, the point is that their skepticism didn’t necessarily produce positive results for the population. So, again, I come back to this idea of not just taking the numbers at face value. Don’t trust me if I say to you this is what they are. Be skeptical, but ask the right questions of the number.

SD: Are you at all concerned about data fatigue?

MC: What do you mean by data fatigue?

SD: We’re just so inundated with numbers, and the US election is the perfect example of that. There were so many polls being conducted by so many different interest groups that by the end of it, I think people just shut off from it. They had a vague sense of what was going on, but there was a lot of contradictory information circulating that would have taken too much time and energy to sit down and process…

MC: I guess I’m not worried about it because I think it’s just something I need to keep in mind when I’m trying to communicate information. I used to do a radio segment, which I was super conscious about because I had three minutes to talk about one number of the week. And if you think about it, even when I’m talking to you, if I was to say “The US population has gone from 330 million people to 350 million (which is not accurate) in the space of 15 years, but for the age group 18-24 it’s gone from….Already, the fact of it being spoken, you’re just like “whoa”. The threshold for those numbers is just so much lower than if it were visual. It might just be because I’m a super visual person. So, I have to think very carefully about which are the numbers that I’m actually going to say out loud and what are the ways around that, so instead of giving the US population in both years, can I just say the US population has grown by 1/5th over the last twenty years? Is it important for you to really understand what it is at now? Because very often when they [people] hear very big numbers, that means nothing. Just really stripping away some of those numbers and assessing how much of it people actually need, but also making sure to tier the information, makes a big difference. Which is really what all journalists do, right? We ask ourselves: what is this bit at the top that you absolutely have to know? And then we give more and more information as people read further.

SD: Your article “Bestiality: which animals are most at risk?” is a surprising and unexpected use of statistics to talk about an issue that most of us have probably not pondered at length. Why was that something you wanted to apply statistics to, and what other topics have you analysed that might seem outside the norm?

MC: My job as a journalist is to look into what I think other people are interested in. I’ve looked at where people injure themselves when they’re grooming their pubic hair. I’m really proud of that illustration. I’ve looked at the prevalence of left-handedness – I did that for International Left-Handers Day. I’ve also looked at cervical dilation, and the way that people’s stomachs and bladders get larger when they eat. I try to use physical objects to help people understand scale, so for that, I used fruit. So, to have a blueberry next to a grapefruit for people to understand cervical dilation is an incredible chart with zero numbers, which is great! I tried to strip away the language as much as possible, ‘cause it also means that non-English speakers are able to get access. But then I guess cervix and dilation are complex words…

SD: One of the statistics that was mentioned in that piece about beastiality was about the prevalence of zoophilia among vets.

MC: Oh, woah! That’s really dark. But how would I get that number? As far as I’m aware, the only way to get that number would be to either look at arrests for zoophilia and look at the occupation of the people arrested. But when people are arrested, their occupation isn’t registered, so that data doesn’t exist. The alternative is to take a survey of vets and ask them, “Are you into bestiality?” And how reliable are those survey results gonna be, you know? You’re gonna get one, maybe, maybe in a thousand, that’s going to say “Yes, I rape the animals that I care for”. No-one else is going to say that.

Anyway, it was a doctor [in that article] that was arrested. It was based on a 2002 survey of 93 zoophiles. Dogs and cows were the most common [animals that people were attracted to], but I couldn’t actually provide proper data because the book that contains the survey costs $200 on Amazon, and the hardback is $2186. If he [the author of that survey] is still alive, I should write to him, because very often they’ll send you the book–because it is a free bit of PR for them.

SD: Since you brought up the chart you created about people injuring themselves while grooming their pubic region, could you talk a little bit about your project, Vagina Dispatches, and what the thinking behind that was? Because it was that project that was so outside the realm of statistics. I mean, statistics were a part of it, but it was also about documenting stories and asking questions. It was really enjoyable to see you explore the topics for yourself and to explore them in a global context.

MC: It’s a four-part video series that I made with a woman called Mae Ryan, who is a very good friend of mine. She was just such a joy to work with on this video series. It’s not particularly stats heavy, but it’s something that I really wanted to make, as a woman with a vagina, who felt like I didn’t know enough about that part of my body. And, I guess, in a really weird way, maybe I’ve always been interested in it. My mom used to be a gynecologist. Maybe we were just raised in a household where vaginas were a big deal. I have a sister, so that’s three of us with vaginas. I don’t know.

SD: Wait, so your mom was a gynecologist (which was addressed in one of the episodes), but you didn’t know a lot about vaginas growing up, despite that?

MC: Yeah…. I say I didn’t know a lot, but I don’t want to suggest for a second that I was any more ignorant than most other women. I was so frightened–when I made that episode–of doing anything that was going to suggest that Western women are empowered. I wasn’t stifled and dealing with all of this stuff just because I was raised in a Muslim household. But, at the same time, I wanna be honest that that was certainly a part of it, that she [my mother] came from a culture that’s radically different in some ways. It’s a fine line to tread. We spoke so openly about all kinds of things. I think she would have been ready and willing to answer any questions I had. And she was, when we filmed the thing [the episode]. But I didn’t know what questions I had until I started making this. I remember I was sitting down and being like, “Do we know everything that we need to know?” A little part of us was like, “This doesn’t really seem like a problem. I don’t really have any problems with my vagina–or I think I know what I need to know.” And it was only from the process of learning that we subsequently realize, retrospectively, “Oh, these are things that I didn’t know.” Like, I wish I had asked about all of these different things.

SD: How has the response been to the series?

MC: Oh, incredible! Just so, so good. We set up an email just for us, where people could write in with questions. And, it’s just been hundreds of emails from all around the world, men, women, different age groups, just saying that this was really important, “Thank you for making it.” I don’t think I’ve ever done anything that I’ve been as proud of. I hope I do something else that I’m as proud of as that. But it’s been incredible.

SD: Are there similar projects that perhaps you’re thinking of developing as a sequel to the Vagina Dispatches?

MC: I don’t know if there is going to be a sequel, to be honest. There were definitely bits that were left out. There were other episodes that we wanted to make that we didn’t get around to. But, yeah, I don’t know…. TBD

Images courtesy of Mona Chalabi