By August 2018, there was nothing left to say about Zimbabwe’s political scene. Robert Mugabe was under house arrest in a mansion somewhere in Harare. The opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai thought he would deliver the people from Mugabe’s thirty-seven year long regime; but there was no promised land, and he had watched Mugabe’s fall only to die right before the elections. Emmerson Mnangagwa had successfully orchestrated the coup against Mugabe and “won” the elections for the still-ruling party Zanu-PF, only to unleash the military on unarmed protestors reminding them that the only thing promised was the same violent rule. Radio stations still played Jah Prayzah and the “Military Touch Movement,” but the music that had once been the soundtrack of the coup was now an acoustic nightmare. In this moment, where an escape from the military would have been welcomed, an experimental poetry magazine named South of Samora appeared instead. It was filled with old liberation poetry that had been published by Zanu and Zapu during the war for Zimbabwe’s independence, poems from known and unknown writers, and photos of the Mozambican revolutionary Samora Machel.

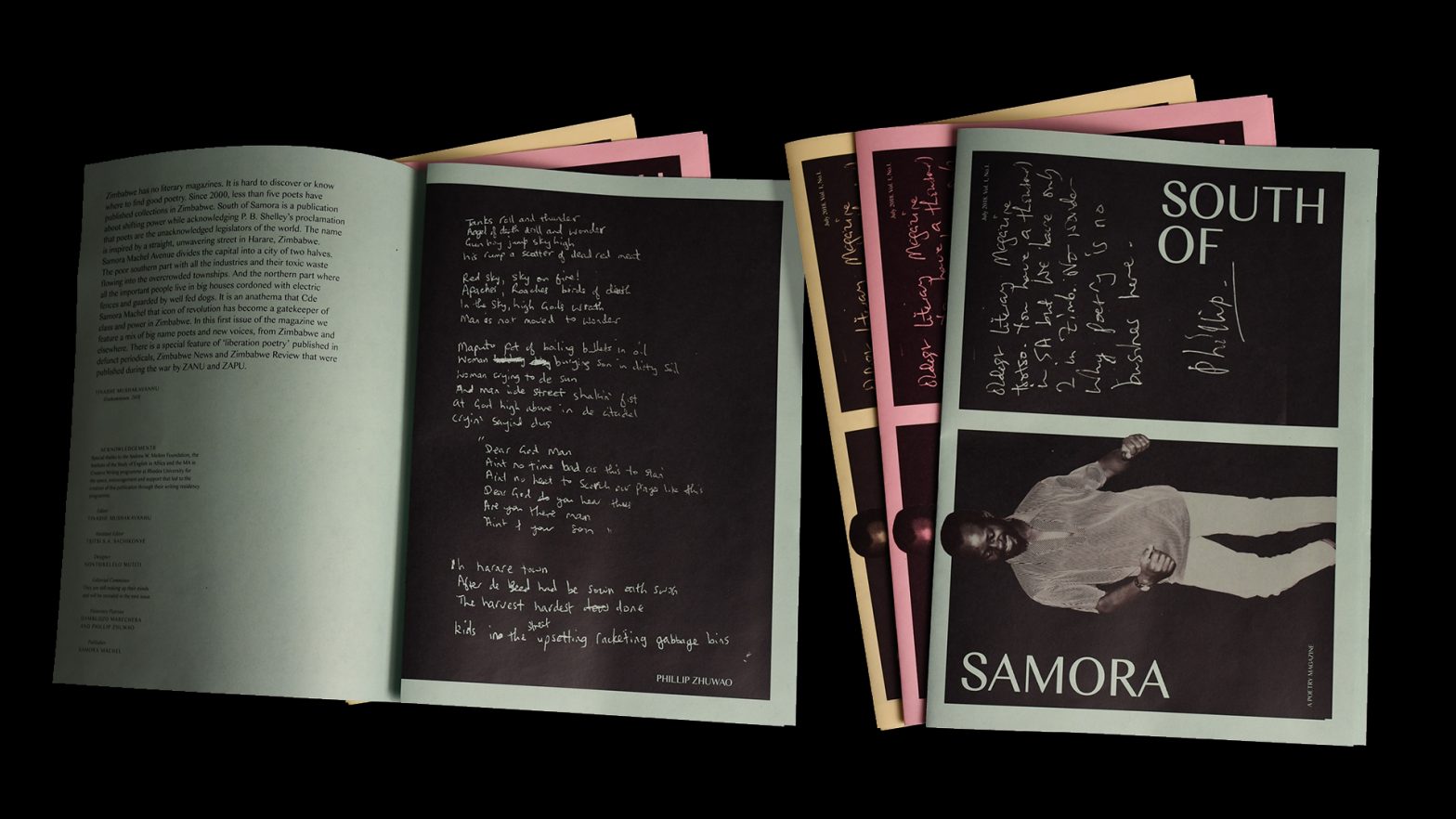

“Zimbabwe has no literary magazine. It is hard to discover or know where to find good poetry,” the editor Tinashe Mushakavhanu wrote in the introduction of South of Samora. The magazine looked more like a zine: it was printed in black and white on regular paper, easy to photocopy and distribute for free without compromising the design. The magazine was made in Grahamstown, South Africa, and I had gotten my copy at the Writivism Literary Festival in Kampala, where Mushakavanhu handed them out from his backpack. Print culture always responds to politics, and South of Samora was easy to circulate locally and internationally, especially amongst the large diaspora that had grown as a result of the mass migration out of Zimbabwe. Named after Samora Machel Avenue, a street in Harare that separates the northern, suburban part of the city from the southern part filled with high density neighborhoods and industrial sites, the magazine questioned the ideological foundations of the country. “It is an anathema that Cde Samora Machel, that icon of revolution has become a gatekeeper of power and class in Zimbabwe,” Mushakavhanu wrote in the magazine.

It was not the war cry against classism and the failure of Zanu-PF to create a more equal society that struck me as strange when I first read South of Samora. The omission of a similar outrage against the prevalence of men in the spheres of politics and poetry was glaring but predictable. It was a reprint of a handwritten note on the cover of the magazine that was unusual:

“Oldest literary magazine Tsotso. You have a thousand in SA but only 2 in Zim. No wonder why poetry is no business here.”

The note was simply signed “Phillip.” Phillip reappeared in the acknowledgments, which at first looked normal: Editor Tinashe Mushakavanhu, Assistant Editor Tsitsi Sachikonya, Designer Nontsikelelo Mutiti. But then got ghostly: Honorary Patrons Dambudzo Marechera and Phillip Zhuwao, Publisher Samora Machel. Three dead men hovered over the question of Zimbabwean poetry, Machel the freedom fighter, Marechera the famous poet, and Zhuwao the less known agitator whose anxieties haunted the magazine. In a moment of literary bravado, the magazine had resurrected a figure I had never heard of whose poetry seemed to have the potential to fuel a revolution in a time of national surrender.

***

The first issue of South of Samora appeared in 2018, the same year that Zhuwao’s first book, Sunrise Poison, was posthumously published, making it a timely re-introduction to the poet. Zhuwao died in 1997 after publishing only a few poems, and it’s still difficult to find any information about his life or the circumstances of his death. Writers often gain recognition through national audiences and Zhuwao’s poetry was mostly published in South Africa, making it difficult for him to be seen. Zhuwao didn’t only fit into one nationality; referring to his Zambian father, his Mozambican mother, and his upbringing in Zimbabwe, he once said, “I have three international identities, an abnormality hard to describe.” By the time Zhuwao died, he had written manuscripts for Sunrise Poison, two novels, and an unfinished second book of poetry. Five years after his death, his chapbook The Red Laughter of Guns in Green Summer Rain, co-written with South African poet Alan Finlay, was released in South Africa. Twenty-one years after the chapbook was released, Sunrise Poison was made available outside of South Africa offering us the first full world narrated by Zhuwao.

“Come/To see my grave I’ve lived on talk/future is my death, my image,” Zhuwao writes in “the rose with marigold blooms,” as if to show that death is more complicated than nationality in a poet’s struggle for recognition. In Zhuwao’s poems nothing happens in the right order, a belief that fueled Zhuwao’s suspicion that he would only be introduced to the world from his grave. Living and dying, waking up and sleeping, day and night are all interchangeable, even in the opening lines of the book:

Tall dreams possess that short zest/ of energy that makes you run all night/ In that dark 27 hours per day/ When 11 pm rings at 7 o’clock.

The poems, like days, go by quickly and erratically. The longest is two and a half pages and the shortest is four lines. The easiest verses to read are those in couplets, but Zhuwao mostly wrote in unconventional stanzas that broke apart as he would burst out in rage, sadness, or a smaller everyday crisis. “(Emily is that the lid for that pot!?)”

Zhuwao saw the world through a red-eyed blur, a consequence of restless sleep from recurring nightmares of being chased by bulls and thrown into black pits. He was also short-sighted. In the only published interview with him, he says, “I mean I couldn’t see what was happening. I couldn’t see the real thing. I couldn’t see the flowers, everything, the knives. So I’d imagine a lot of things in my head…In class, I could see nothing on the blackboard, so I failed my exams.” As a self-taught poet, not taking the rules of the “english sanguage” seriously became his aesthetic:

When they began talking of digris She looked at me at my empty silence but you write write poems how come you got no degrees?” -“i want out!”

Zhuwao would change degrees to “digris”, horizons to “horroizons”, and from the debris and horror of that blown up language, he created poetry.

Words were shattered as Zhuwao tried to find the visual language to think about life in the aftermath of the liberation war. Describing his childhood, Zhuwao said: “I saw bullets and blood. My father was a soldier. In 1987, to try and forget the terror of Inkomo Barracks and the panga knives, we shifted to Kuwadzana in Harare.” Inkomo Barracks was a headquarters for the Rhodesian army, and later the Zimbabwean military forces after independence in 1980. It is not clear when and on which side Zhuwao’s father fought, but Zhuwao became obsessed with mixing imagery of bombs and botanicals: “blood dribbled from the blossoms,” “Fractured marigolds,” “jacaranda’s blood,” “smouldering cemetery flawas,” “boquets drop blood.” Sometimes Zhuwao wanted to “rescue the flower from the rubble,” but he couldn’t help but spell “boquets” to sound like buckets. Death was overflowing, and life felt both fragile and beautiful.

When I read Sunrise Poison in August of 2018, twenty-four years after Zhuwao had finished writing the book in 1994, his poetry felt current not only because Harare was still on fire. Zhuwao created images where violence was absurdly placed next to the mundane. His work showed how poetic forms mimicked a disorientation similar to the effect of the rapid imagery that narrated Mnangagwa’s transition into presidency from the coup in November 2017 to the elections in July the following year. Watching the transition from the diaspora, the news kept breaking through a frenzy of social media highlights: Mugabe having tea with army generals, Mugabe at a graduation ceremony handing out diplomas, a powerless Mugabe sitting on an ugly sofa, Mnangagwa’s scarf, billboards burning in Harare after elections, six protestors reported dead.

“Zhuwao’s work has this unforgiving, almost schizophrenic quality to it: it’s like manic cinema and it’s all happening at once, and when you’re done, it’s as if something has exploded: a world view, a disaster, an emotion, a small room where a man slept, alone,” the poet and illustrator, Megan Ross, said about the inspiration behind the cover image of Sunrise Poison. The image has broken bits of roses, razor wire, notebook paper, and black clouds. The clouds could be smudges of ink or an incoming storm, both warnings that no violence goes unnoticed.

***

Literature is hard to circulate in the midst of domestic wars, and for years Zimbabwean writers have been forced to publish outside the country. Displacement can make the place where your intellectual property is stored and circulated your home, and those who have access to your memories your people.It is not surprising then that Zhuwao is sometimes called a South African poet. In South of Samora, Mushakavanhu and Mutiti create a Southern African community with poets from the region as an acknowledgement of how inseparable our histories are. Yet, Mutiti’s designsalso place Zhuwao within a black Zimbabwean literary history, where his story can be told alongside Marechera’s (a poet whom he loved).

Marechera’s poem is the only one in the issue that is printed from the newspaper clipping in the Sunday Mail where it was first published. Above Marechera’s poem is a picture of him in a plain white tee, and the clipping makes him look like a literary celebrity being exposed by a tabloid magazine. Zhuwao’s poem, on the other hand, appears in handwriting and it is the only one in the magazine that looks like an early draft. Some words in the unnamed poem are crossed out, and I can’t quite make out the last stanza. Despite their distinct and almost oppositional careers, both writers died young, Marechera at thirty-six and Zhuwao at twenty-seven. Neither got to see all their books published, and not all of Marechera’s work can be found in bookstores in Harare, where the stories of his hard living are remembered more than the material of his poetry. In different ways, both poets feel distant not only because of how their work circulates, but also because they wrote about what it meant to be outcasts who created their own rules to live by.

It makes sense to read Zhuwao and Marechera together for their shared anarchic sensibilities, but they should also be read together for the way they thought about anarchy through sexuality, or what Zhuwao called “anarchy anus.” When Marechera was writing Black Sunlight he became obsessed with the sexualization of the nation. He said in an interview with Alle Lansu:

“At the same time, a very heavy element in Black Sunlight is this idea about sexuality. Everything political becomes personal, everything personal becomes political, but the four are in a state of continuous tension, and therefore almost everything one says or does reeks actually of sex. A bullet can be a heavy sexual image. A bomb can be like the eruption of sperm in the womb. Most of the people I was living with were people who rejected traditional sexual roles and accepted sexuality as a liberating force in itself.”

Zhuwao, who described himself as being on a “Marechera hangover,” would also write about Zimbabwe as a place where the bombed and the blooming landscape was filled with sexual innuendo.

In “Unicorn at Zim b awe loins,” Zhuwao blew up the nation’s name to make a spectacle out of Zimbabwe so that he could look at it and himself with awe. He named different neighborhoods in Harare, Chitungwiza, Kuwadzana, Lomangundi, and Highfield, and traced his life as he moved from place to place while pointing out the “Dragon bearing semen splushed into the city.” For Zhuwao, migration was not just about leaving the country, but about the ways that your own city could alienate you.

As Zhuwao critiqued the state, he used graphic images of women’s bodies to think about how violence was sexualized. He wrote about the destruction of Harare as the “rape of harare” and sometimes the red of bloody botanicals was the “red of virginity torn.” The woman’s body is all over the book from titles like “i am her opened legs” to “Irene’s iron pearls,” in which he writes,

She strikes the pose and clutches her buttocks and goes berserk on my pen then howls like hippolytus as I drive into her.

There are times when Zhuwao’s “anus anarchy” is shameless, uncensored, and almost freeing. Other times, choosing to be carefree meant that Zhuwao blew up everything around him but suspiciously left intact tropes of women. Confessing either his unwillingness, inability, or indifference to write beyond the sexed female body he wrote, “I just can’t cunt explain my poetry.” It is in these moments, when he refuses to test the limits of language and finds comfort in his masculinity that I am reminded of how little we have in common. The distance of time between us becomes clearer, the distance of gender wider, and the distance of death deeper with the somber knowledge that this is all the poetry I could ask from him.

***

When I first looked at South of Samora, I was captivated by the image on the cover of a man dancing alone. I shared the photo with friends who knew Samora Machel, but none of them recognized him in the picture. There were other photos of Machel in the issue, including a copy of Machel’s liberation membership card and a photo of him giving a speech, but without his uniform or a suit he looked like any man enjoying a night out rather than the man who became the first Black president of Mozambique. Zhuwao’s note was placed next to Machel’s photo, as if the two men shared equal roles in influencing society. “South of Samora is a publication about shifting power while acknowledging P.B Shelley’s proclamation that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” Mushakavanhu wrote about his ambitions to reimagine hierarchies through a small magazine.

At the end of November 2018, I saw Mushakavanhu in Boston for a panel on Zimbabwean politics and literature that marked the anniversary of the coup. Still walking around with a backpack full of magazines, he gave me a new version of the first issue of South of Samora. The magazine was now on thick grey paper and the text had been changed from black to blue ink. Where once “poetry magazine” had been written in the margins, now it said “politics magazine.” Yet, the most glaring change to me was that Zhuwao’s note, which had initially been next to Samora Machel’s photo, was now missing from cover. In a few months, the magazine had shifted from something that looked rushed and urgent to something beautiful that could be collected and displayed. “Red sky, sky on fire!” Zhuwao had written in his unnamed poem in South of Samora, but in the redesigned issue the words felt less like a war cry and more like a reminder that Zhuwao might have never seen himself as the hero I imagined him to be.

***

“I mean I can’t go to war and fight for anyone. I don’t even think I’m patriotic. I don’t think I would call that a selfish perspective,” Zhuwao once said when he was asked if he would ever join the military. For him, poetry was a better struggle, a “blank verse in freedom’s thinking.” Poetry was the fight to face violence and unflinchingly record it, to destroy language and create a new one more durable than his own body, to immerse himself in his art so that he could honestly say “in their short lives/poets live longer.”

Cover image – South of Samora: A Journal for Poetics, Vol. 1. Limited edition, laser printed, black on coloured copy paper, 8 pages, folded dimensions 8,25x 11,75 inches. Second printing. (Interior spread, left, handwritten poem by Phillip Zhuwao. Front cover, right.)

This piece is from our latest print edition: Is This the End?, which you can buy here.