This article is part of LOCAL, a season celebrating community support structures in Sheffield, Birmingham and London.

On the easternmost part of Great Ormond Street, large terracotta pots line the pavement, each one bursting with shades of green and clusters of pink and orange petals. The street is narrow so the trees on each side create a canopy, sun dappled leaves letting in streaks of light. It is very easy to romanticise this neighbourhood. Cobbled streets, quiet bucolic mewses, and ye-olde-village type architecture tucked between High Holborn and Euston Road. The pub next to the bakery, opposite the GP and pharmacy, down the road from where the post office used to be. Three youth centres in walking distance.

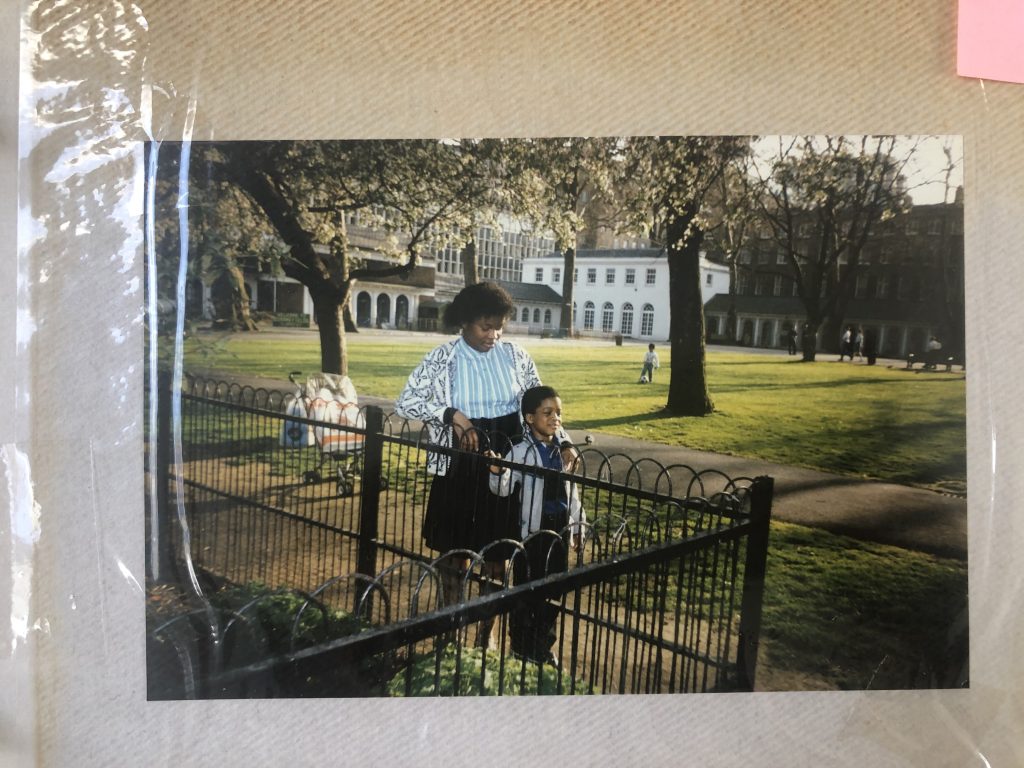

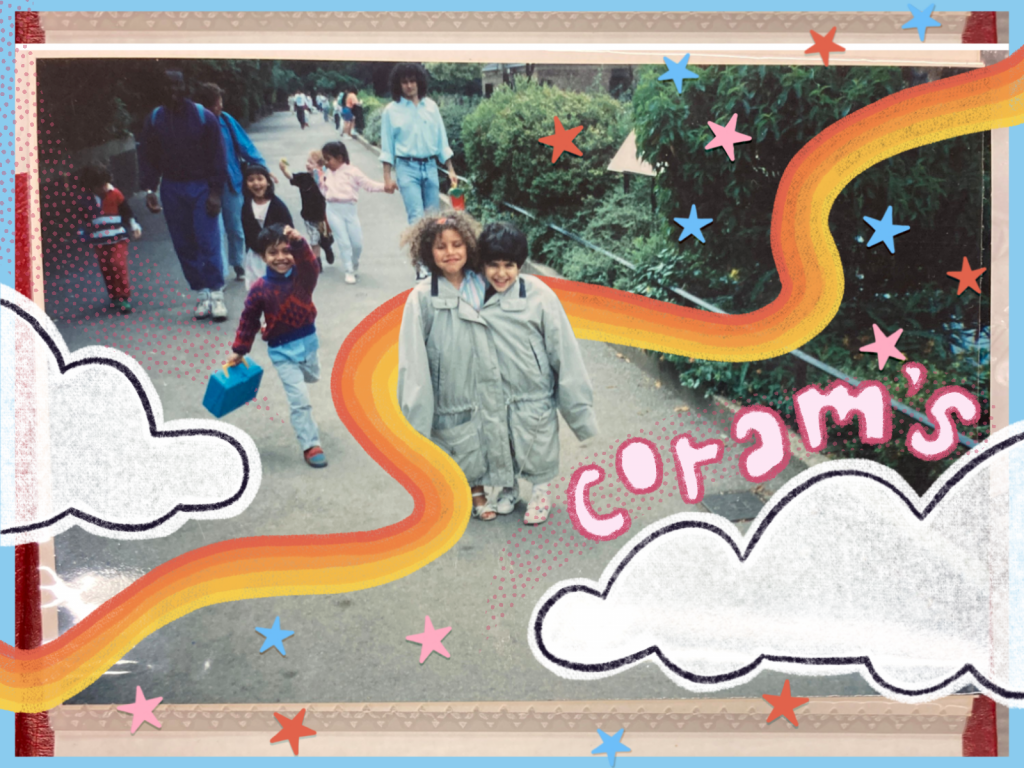

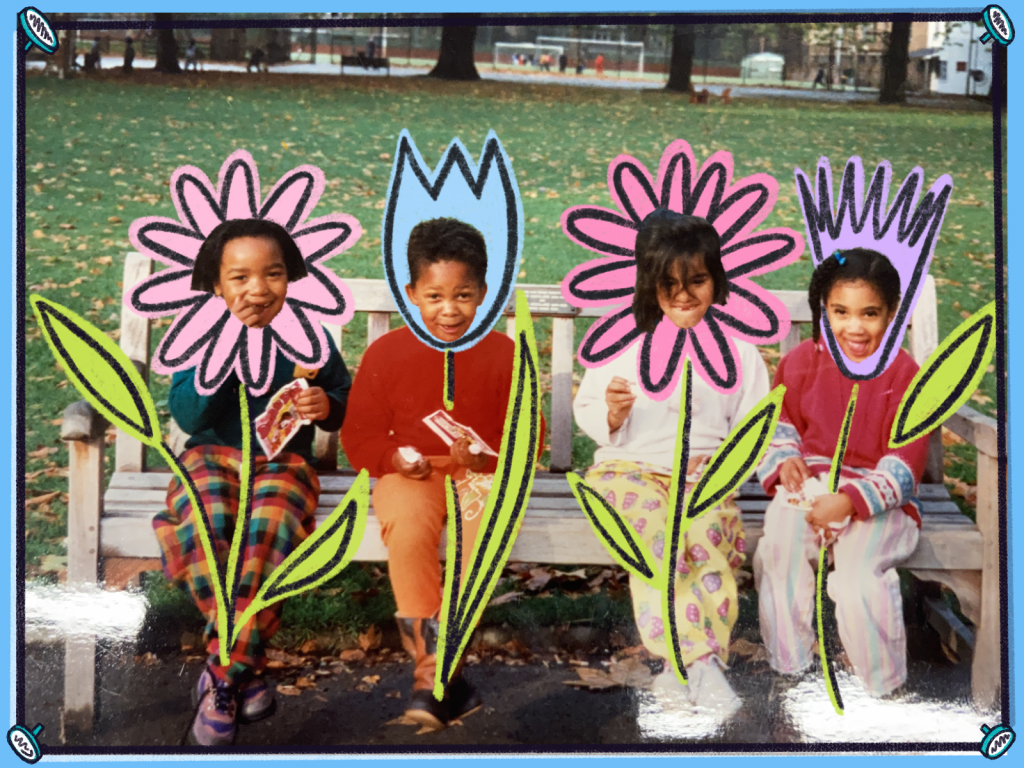

I grew up in this neighbourhood in the 90s and early 2000s. Most days after school, my brother and I would rush home to an empty flat to change out of our uniforms and into our park clothes. We’d grab a couple packets of crisps each, promising to tell our mum we just took one. Since he was older, he’d lock the door and hold the key until we got to the lifts, but since I was more responsible, I’d take it off him once we left our block. If we wanted to add sweets to our snacks – 10p rainbow dust and 5p drumsticks – we’d stop off at Superbuys en route to Coram’s Fields, passing through Great Ormond Street on the way.

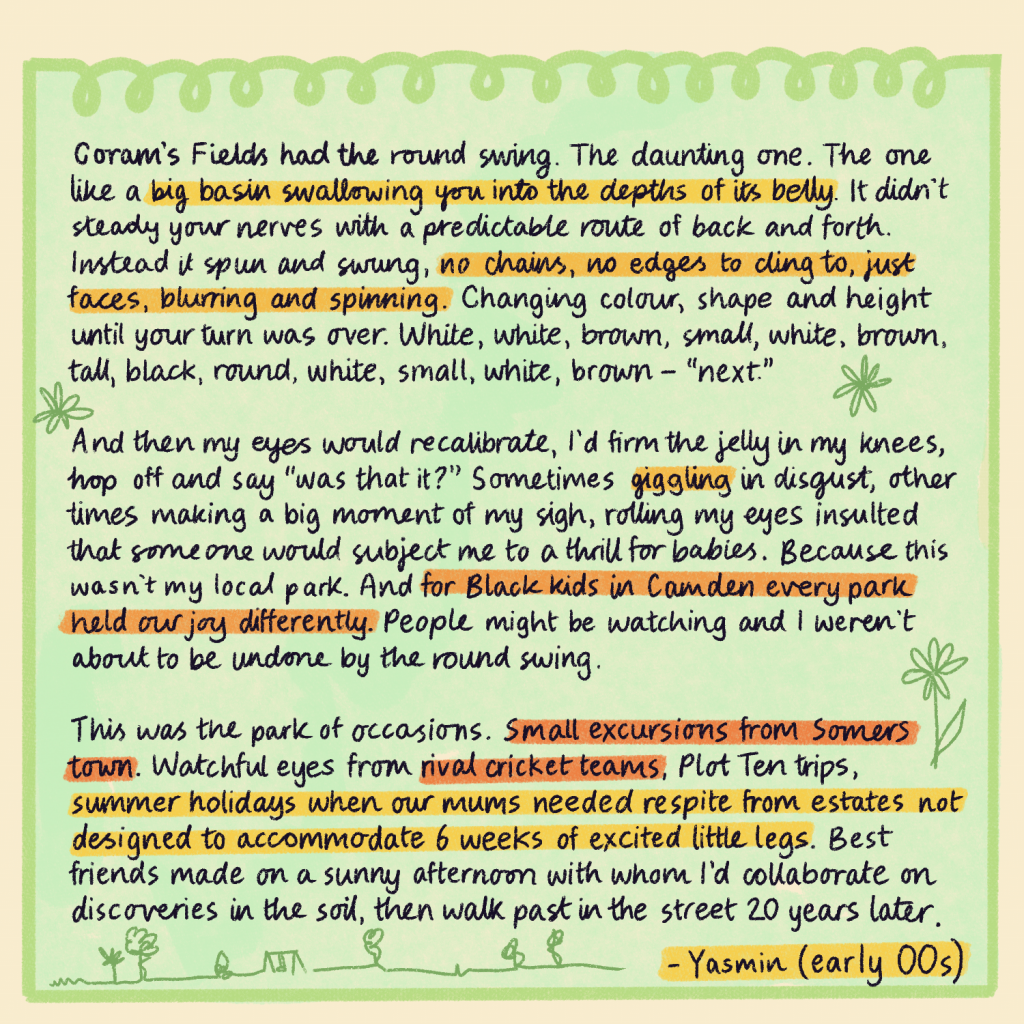

Coram’s was a microcosm of our local society, each local primary having regular representation. St Joseph’s contingent was mostly white, sounded like Eastenders, always had the latest scooters and Gap hoodies. The Christopher Hatton lot were bohemian with names like Grey. Argyle kids were rumoured to carry shanks, but were mostly a fun time. And St Georges, we were savvy but lawless, blocking up the tunnel slide and taking over the zipline because we felt like it. Coram’s gave us a space, though temporarily and unevenly, to be just children. Most of us were kids of immigrant parents and grandparents, living in social housing with caregivers who worked multiple jobs. A lot of the park staff grew up in the area, too. And even if they didn’t, they still looked like us, knew how to talk to us, and how to show us they cared.

In this environment, we learned how to move through the world. We’d express all our thoughts and ask all our questions. We’d look out for ourselves and each other, building the kind of confidence rarely encouraged in us in public space. As we got older – our bodies getting grown, our self-awareness changing – we spent more time in the youth centre than the park itself. And we were better for it. Despite the wealth of Coram’s surroundings, a third of young people in the area lived in poverty, and faced the same dangers poverty begets across the city. The youth centre provided place and purpose, at least temporarily, and it was the staff, the youth workers who kept showing up, who built and guarded the parameters for our momentary freedoms. It is the youth workers who are still making Coram’s what it is today.

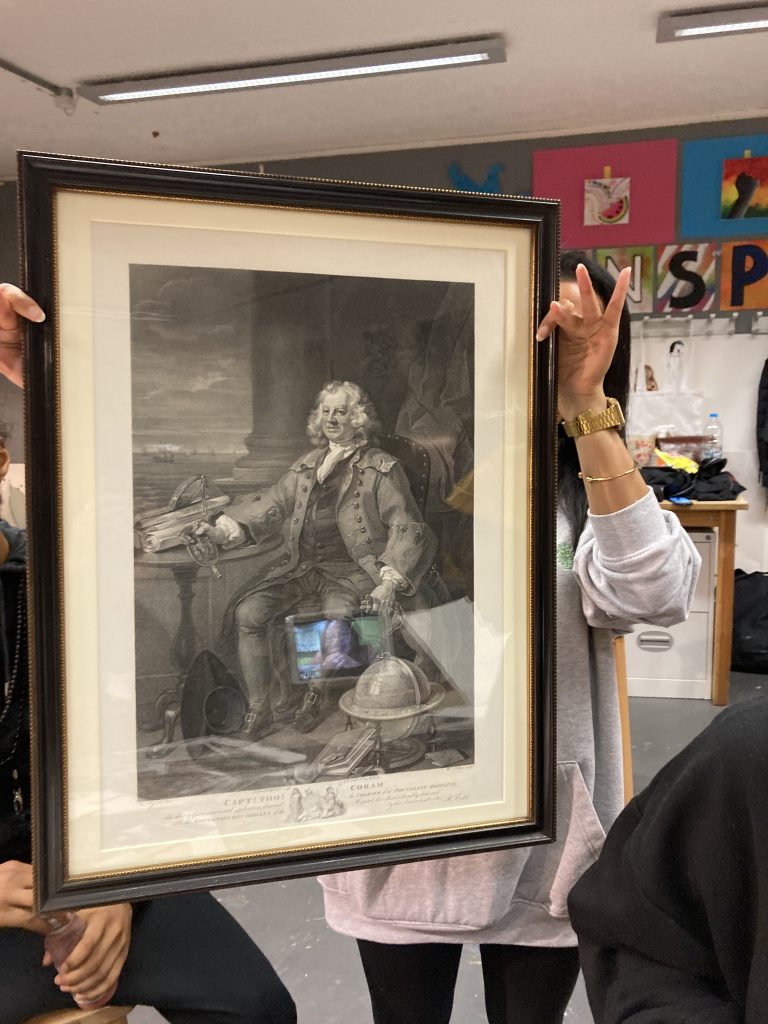

An Englishman named Thomas Coram made a fortune. His father had been a sea captain and he stepped into that legacy, amassing wealth through the late 1600s to mid 1700s. The demand for shipping services was booming at that time, and so Mr Coram became very rich.

Naturally, Mr Coram’s work took him overseas. He lived in Massachusetts for a while and even opened a shipyard there, but after roughly a decade he decided it was time to move home. He collected his earnings from facilitating the buying, selling, and transporting of Africans to the Americas as slaves, and Mr Coram eventually settled in Rotherhithe, London.

On his business trips into the city, he would see scores of abandoned children, dead and dying on the streets. It made him sad so, after years of effort, he got a charter signed by the King for the Foundling Hospital, the UK’s first incorporated charity with the mission of taking care of London’s most vulnerable young people. This process of distribution – systemically incremental and reifying of hierarchy – would become philanthropy. And the site of the Foundling Hospital would become Coram’s Fields.

When Resolve Collective and Skin Deep had our first meeting in August with Dershe Samaria, a youth worker at Coram’s Fields Youth Centre, we started by comparing names for overlap in the people we knew. Very few rang a bell: not Rehad who worked the gate, or Ann Marie who led dance classes for the summer ‘03 talent show.

“Hold on,” Dershe said, getting up and heading out the room.

She came back with a familiar looking man around my brother’s age, and after a moment we realised who we were. He’d lived on my road growing up, opposite my primary school. His mum used to do my hair on the weekends and his sisters would walk me to the corner shop. These memories flooded the room, and many more I’d been too young to remember. It was unexpected, a beautiful reminder of the community that showed me what it meant to be local.

A few months later on a rainy Tuesday evening, Dershe laid out hundreds of photographs and newspaper clippings in the art room at the youth centre. Skin Deep and Resolve were hosting a workshop with the young people at Coram’s, the idea being to resurface hidden stories that had unfolded in the spaces they now frequent. Dershe had found boxes and boxes of archival material sitting untouched in back rooms, and even before the youth arrived we were already planning a longer term restoration project.

Dershe’s official title at the youth centre is Employability Lead, helping young people find work opportunities. But so much of her role is about being a trusted and caring figure in their lives. They told us about their own journeys through the centre – some coming in from Kilburn, others from Hackney, some experiencing houselessness – and all said they keep coming back because of Dershe and the others like her.

I don’t remember us having an art room when I went through the youth centre, and our recording studio was definitely more broom closet. I was also much younger than the people in our workshop when I would go to the youth centre, reminding me both of the large scope of young people’s needs being met by youth workers, and how much of youth work ends up being a remedy for an education system that can so easily alienate and traumatise young people.

It is difficult to quantify the countless and complex effects each centre, each club, and each youth worker can have on young people’s lives in this country.

And so it’s hard to truly calculate the harm produced by 4,500 youth worker job losses in the last decade.

Or the closure of 763 centres across England and Wales in that same period.

From 2010 to 2019, the government cut funding for youth services by 70%. Meanwhile, local authority spending on crisis intervention for young people has shot up. A state that endangers young people by drastically depleting their support structures, at the same time as the richest 1% pull further and further ahead of everyone else, can do so in part thanks to the kind of wealth and power hoarding that philanthropy sanitises.

As such these statistics barely capture a fraction of the rippling consequences of structural abandonment of young people.

Before we end our archiving workshop with the young people at Coram’s, I try to get them to do a little writing exercise with me. It’s hard; they’re all so engrossed in the pictures and not particularly interested in writing about feelings. But I persist, and quickly ask them a few questions.

What do you do at Coram’s?

“Connect. Reflect. Visit Dershe and catch up.”

What’s something you’ve done or made at Coram’s that remains important to you?

“Showcasing my poetry at October Gallery. I was able to reconnect with an old friend and construct a song that WE did together”

What does safety feel like?

“Safety feels like not having to feel like you’re just ‘surviving’ and ‘existing’ from day to day… a balcony at night in a city somewhere that’s not London with a great playlist.”

Why do you keep coming back to Coram’s?

“Dershe. Because she always knows what to say when it (everything) goes bad. I like to come back and see what new adventures and opportunities she has for me. Even if it’s nothing career related, a chat and comfort is always on the table.”

Many thanks to the contributors who shared their personal memories, to the young people who took part in the archival workshop, to Dershe Samaria, and to all at Coram’s Fields.

Tamara-Jade Kaz is a queer Black feminist creative, facilitator and trainer based in London. Website / Instagram

This season of storytelling took place over six months, across three cities and involved over 40 contributors. We believe that our communities’ stories deserve this level of care, time and attention. If you agree, become a Skin Deep member and support us with a small monthly donation.