In October 2017, Linda Brogan put on a hard hat and started digging. The site of the playwright’s archaeological excavation was a night club that had shut its doors three decades earlier. Brogan wanted to burrow into the earth to find artefacts and clues about a place that had been buried to make way for modern Manchester.

The Reno was a small, dark club in a basement underneath a bookies in Moss Side, one of the longest established Black communities in the UK. For the Mancunians who walked through its black door and down the steep stairs into its belly, it conjures myriad images and memories. The club was not glamorous: the toilets were notoriously disgusting, and it could be dangerous for outsiders – you might be relieved of your money if you weren’t streetwise. But for its regulars who paid their £2 entry, The Reno offered the cutting edge of Black music and culture, and a sanctuary for many in Moss Side.

In 1986, The Reno would be demolished – it was one of the last remnants of the old Moss Side and Hulme, areas that were razed as part of “The Manchester Plan”, a forty-year project of urban renewal designed to create a modern city. The Reno and its clientele didn’t fit with that new vision, which saw hundreds of Black Mancunians forced to sell their homes in the name of progress. But over the two decades of its existence, The Reno had delivered its own vision of the future. The resident DJs, including Persian and Hewan Clarke, played futuristic Black music, from underground soul to the paradigm shift that was house music. The Reno served as a transmitter of Black music, its sounds rippling out across Manchester’s cultural landscape and beyond. Without it, the UK wouldn’t sound like it does today.

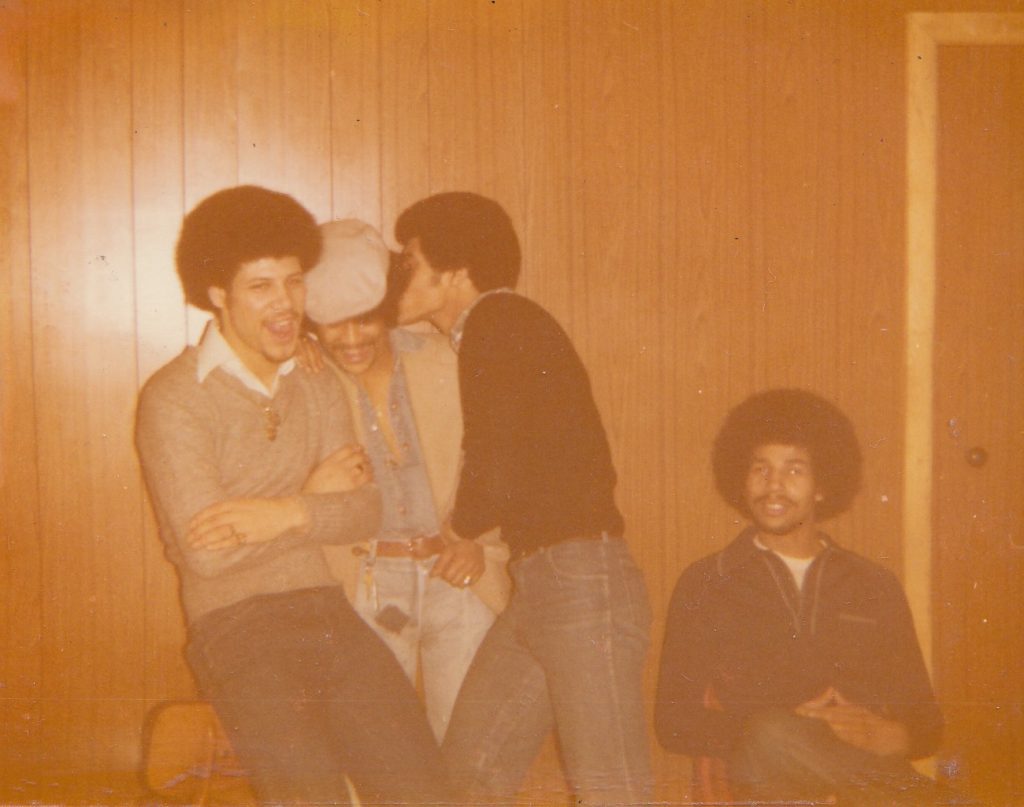

The Reno was in the part of Moss Side beyond Raby Street that Brogan considered to be “naughty”. It was where cool people and the kids from the tenement blocks went, those children whose parents might not have been around to tell them not to go. Brogan’s family was a typical one from the area: her mother was Irish, from Limerick, and her father was Jamaican. She shouldn’t really have been going to The Reno, and she knew it. To the teenage Brogan, the girls at the bar with their colourful collars, V-neck jumpers and Levi’s 501 jeans “exuded cool”, and as someone searching for her own identity in 1970s Britain, she wanted a part of it.

But Brogan wasn’t the only person who was aware of The Reno’s transgressive reputation. She first walked through The Reno’s black door in 1976, when Manchester received a new Chief Constable named James Anderton. Known as “God’s Copper”, Anderton once claimed his job was “an extension of his Christian mission to raise the moral quality of life”. When he took up the post of Chief Constable, Anderton began waging war on those who he considered remorseless sinners.

Anderton policed premises suspected of selling pornography, public toilets where gay men cruised, and illicit blues and shebeens in the area. Once appointed to the top job, The Reno and The Nile were firmly in his sights, with violent raids a common occurrence during his reign. The right-wing Daily Telegraph ran a story that called him “Britain’s toughest policeman”. For the Chief Constable, The Reno was little more than a “vice den”. He would never be able to comprehend the club’s importance as a cultural melting pot, and its significance in Manchester’s long and largely forgotten Black history.

The Reno’s owner was a Nigerian, Phil Magbotiwan, who came to Manchester from Lagos in the 1930s. Like many Black arrivals, Magbotiwan had been attracted to the city by the prospect of work in its factories, and he found employment at Dunlap’s rubber manufacturers. Some of Magbotiwan’s own experiences in Manchester showed why venues like The Reno were so needed. When contemplating the idea of buying a club, he went to the Little Alex pub, not far from the site of The Reno. The landlord refused to serve him, nodding toward the barrel where people threw their dregs and pint ends. “N*****s drink out of that,” he was told. Magbotiwan promised the man that one day he’d start his own club, and the man would regret what he’d said.

When Magbotiwan first bought The Reno, he couldn’t get a licence, so he turned it into a hostel, offering beds to African seamen who could get a hot meal and buy Johnny Player cigarettes. In 1963 he was finally granted a licence and The Reno opened for business. A few weeks after Magbotiwan’s doors opened, the landlord of the Little Alex came over to inspect the competition. He walked up to the bar, not realising who the new owner was, and ordered a Red Stripe. While serving him, Magbotiwan asked the man if he remembered his visit to the pub across the road. The man couldn’t recall his face at first but then recognised who he was and apologised. “Anyone can make a mistake,” said Magbotiwan, who forgave the man.

The Reno was open seven days a week. During the afternoons, it served as a social club, with many of the older African and Caribbean men gathering to play dominos, pool or cards. But on the weekends, it became a bustling club, full of younger Black Mancunians. Artefacts unearthed during the 2017 dig reflected its speakeasy atmosphere. The amateur archaeologists gathered at the site dug up champagne bottles, a pair of flares, discarded records, wallets, lipstick tubes and even a bag of weed.

Anderton might have detested the “ungodliness” of The Reno, but his officers regularly frequented the club and were happy to take bribes. The club was supposed to close at 2 a.m., but Magbotiwan had an arrangement with a group of officers who would come to the club in the daytime to pick up an envelope filled with money. They’d sometimes go to the Magbotiwans’ house.

Lisa Ayegun remembers two police officers coming to the door in suits. “They’d call my dad, and he would say put them in the lounge,” she says. Her father would sit upstairs in his “money room” before coming down with a payoff that meant they could stay open until 6 a.m. – crucial for the club’s success as an after-hours spot. To keep up appearances, the police would occasionally raid the club, which would infuriate Magbotiwan. “When they’d be gone he’d be like ‘fucking bastards have had their fucking money’,” says Ayegun.

While preventing entry on the basis of skin colour was illegal, Black people – and Black men in particular – were still finding it was impossible to get into many venues in central Manchester in the early 1980s. “They did it by using simple things,” remembers Bolaji Laurance, whose mother Kath Locke would co-found the Black feminist group the Abasindi Collective. “You can’t come in if you’re not with a girl; you can’t come in if you’ve got an Afro or an Afro comb. So The Reno and The Nile became popular simply because nobody could get into [venues in] town.”

The DJ who gave The Reno its reputation was a Jamaican man simply known as Persian. The music policy at The Reno when Magbotiwan set it up was initially Blue Beat and ska, but in 1967 Persian was hired as resident DJ and had his own vision.

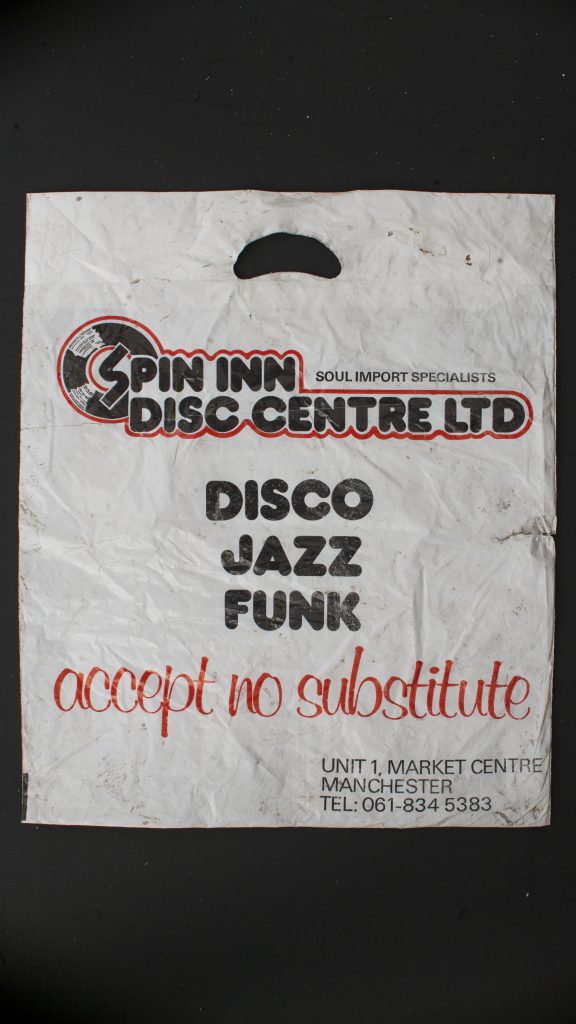

Persian’s skill was in playing mid-tempo soul tracks, often album cuts that others had ignored; tracks like The Crusaders’ ‘Stomp and Buck Dance’ and Earth, Wind and Fire ‘Reasons’; or Bill Summers’ ‘Summer Fun’ and the more sultry ‘Weaver of Dreams’ by Freddie Hubbard. “The Reno was deep,” says Hewan Clarke, who would succeed Persian as a resident DJ. “If there was a new album by Brazilian percussionist Paulinho Da Costa which had a jazz-funk dance track that was popular in the clubs in town, there’d be another track on there with a killer bassline and nice melodic parts,” recalls Clarke. “Persian would play that kind of stuff.”

Want to support more storytelling like this? Become a Skin Deep member.

Persian’s influence was huge. Other Manchester DJs would come down to hear him play, including Clarke, the musical tastemaker John Grant and former Northern Soul spinner Colin Curtis, who opened the club Rafters in 1978 – one of the first city centre clubs to operate an egalitarian door policy. “There was one DJ from The Reno who affected what we played and that was Persian,” says Curtis. “He was a connection between what was happening at The Reno and what was going on in the city centre.” Slowly, the songs that were hits at The Reno started to seep out onto mainstream dance floors across Manchester.

By the middle of Persian’s tenure in the mid-1970s, the club’s great music and loose, illicit reputation was attracting some famous faces. Muhammad Ali visited the club after Magbotiwan travelled to Canada to watch a fight and told the boxer about Moss Side and his club. His daughter Lisa still wears the golden gloves pendant Ali gave her father on a necklace. There was an apocryphal rumour that Bob Marley once attended. Tony Wilson, who would change the city with his TV show on Granada that gave exposure to bands he’d then release on Factory Records, had his stag do in The Reno. Other Reno regulars included the outlaw white snooker player Alex “Hurricane” Higgins, who would play Magbotiwan at pool. Higgins, whose own hellraiser reputation made him a pariah in polite society, once told Hewan Clarke he preferred socialising with Black people “because my people don’t want me”. The club was for those on the margins of society; Persian saw The Reno as being like a speakeasy that he’d read about and seen in the American prohibition films he’d watched back in Jamaica.

During the summer of 1981, where large-scale civil unrest spread throughout the UK, there were three nights of looting and violence across Moss Side, largely in reaction to the police harassment Black Mancunians were facing. Trouble had originally erupted outside The Nile, the reggae club that was above the betting shop and The Reno, in the early hours of 8 July 1981.

During the disturbances, Anderton, who declared “guerilla warfare”, had assembled more than 500 officers to clear the streets of Moss Side, headed by his controversial and hated Tactical Action Group who drove around in Land Rovers and were known for their fondness of using Sus laws to detain young Black men. On the second and third nights, Chief Constable James Anderton’s shock-and-awe approach resulted in arrests and horrible injuries. Around 60 per cent of the people arrested during the disturbances were white, yet most of the coverage focused on Black Mancunians.

The events of July 1981 made The Reno even more important to the young people of Moss Side – a place of safety and escape from the dangers that awaited them on the streets outside their homes. Persian was in Hamburg. He’d taken up a three-month residency at the Third World Club, a forward-thinking soul venue in the German city. On his return from Hamburg, Persian decided to pull out Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway’s ‘Back Together Again’. He thought the song – a typically mid-tempo soul affair – would be a tonic for the dancers, many of whom had been caught up in the unrest. As the needle hit the groove and the crowd heard the lyrics, which referred to people persevering through the “hard times” before being reunited, there was a cheer, and people banged their glasses on the table and slapped the walls of the club: their selector was back.

Linda Brogan went to The Reno one last time in 1986. She’d been a near-weekly regular between 1976 and 1982 – Persian’s imperial phase. As she walked in, something felt amiss. “Persian wasn’t there,” she says – instead, his successor Hewan Clarke was behind the decks. “And the music was different – it was heaving in an odd way.” Her club had disappeared. The basement seemed darker, the crowd was younger and the music was harder. What Brogan had heard was the future: house music had arrived in Manchester – imported by a new generation of DJs. The four-to-the-floor beats sounded like “Black heavy metal” to her, the antithesis of Persian’s downtempo style. What Brogan witnessed was both the end of The Reno and the birth of house music.

The established folklore is that four intrepid Londoners: Danny Rampling, Johnny Walker, Nicky Holloway and Paul Oakenfold, went to Ibiza in 1987 and imported house, while providing the building blocks for the rave scene in the UK. But before acid house went mainstream, Manchester’s Black dancers were the first to interpret the sounds that Chicago DJs like Ron Hardy and Frankie Knuckles were playing across the Atlantic. The Reno, with Clarke’s “Black heavy metal” that so disturbed Brogan, was the testing ground for the biggest youth movement the UK had seen since the 1960s – acid house and rave.

When Linda Brogan looks back at The Reno it’s with a mixture of nostalgia and sadness. Her club had been shut down by the council by 1986, and her fellow regulars would face testing times in the 1990s as hard drugs – and in particular, heroin – shot through Moss Side. The close ties and intense friendships among the group meant the drug went through The Reno crowd “like wildfire”, Brogan said. When you look at the club’s online memorial wall, many of the punters, who would today have been in their fifties and sixties, are long dead – several dying not long after the club was demolished. The people who dug up the club’s foundations weren’t just former regulars, they were survivors.

Standing on the site of The Reno today, a little patch of grass with a foot-high wooden fence that cordons it off from a footpath, it’s hard to imagine what once was. The row of shops that sat next to the club are all but gone; as is the reggae club, The Nile, which was upstairs. The only remnants are crumbling buildings and a scrap yard across the road. On this patch of grass – flanked by the Heineken brewery’s chimneys and Princess Parkway, which hums with traffic coming in and out of the city centre – Brogan, and dozens of former regulars, gathered to help with the dig in 2017. With assistance from the archaeology team at Salford University, the survivors burrowed into the dirt and found the club’s foundations.

During the weeks of the dig, Brogan got the resident DJs back together and invited the old crowd for a party held on the dig site under a marquee. Former regulars chatted about the old days and danced to the tracks they loved from the 1970s played by their DJ – Persian. Brogan interviewed many of them to create an oral history project, while a memorial wall was posted online to commemorate those who’d passed away. For a moment, a forgotten part of Black Manchester’s history, one which linked radicals, hustlers and artists, was exhumed.

This is an edited extract from We Were There: How Black Culture, Resistance and Community Shaped Modern Britain (Bodley Head: Penguin, 2025), available to buy now.

Stay in touch. Subscribe to Skin Deep’s monthly newsletter.

All images courtesy of Linda Brogan.