You jump-start suddenly from a horror scene unfolding on your social media timeline. A chilling glimpse into the mass trenches of a cobalt mine in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). As you loom over with a bird’s-eye view, there’s something unnerving about your sudden proximity to it all. To this mining enclave the size of a small village. To these men, women and children – so many children – toiling in the red earth, scouring through toxic waste for precious metal. These days, human suffering all too easily takes on a new and perverse rhythm – genocides live and breathe by day, producing fresh horrors by night – and so you are compelled to keep watching.

And then something clicks. A horrifying realisation. An emptying pit in your stomach. Smartphones, smart cars and smart homes, all synced up courtesy of Apple, Tesla and Google Assistant. Apple Watches and iPhones, MacBooks and Microsoft 365, powering our lives. Artefacts of an unceremonious kinship, implicating us all in a chain of supply and demand, exploitation and extraction, advancement and catastrophe. The engineering of cobalt doesn’t just make all of this possible – it makes it necessary. In times of crisis, we turn to the comfort of our devices, and so the vicious cycle continues. In the words of Frantz Fanon, “The cause is the consequence.” You consume more, before it can consume you.

“Smartphones, smart cars and smart homes, implicating us all in a chain of exploitation and extraction, advancement and catastrophe. In times of crisis, we turn to the comfort of our devices, and so the vicious cycle continues.”

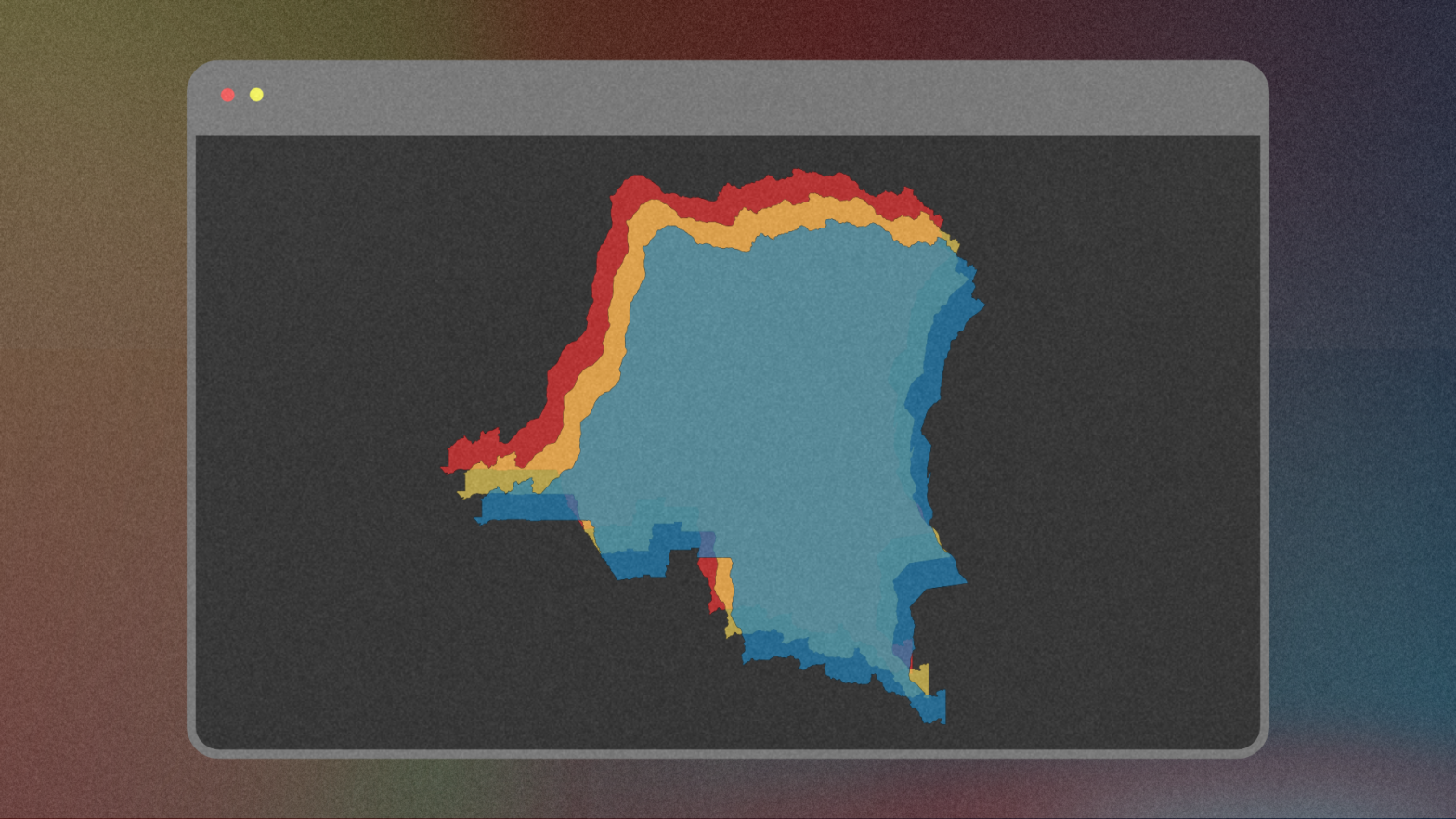

A genocide is happening in the Congo that is far from silent. Since the DRC achieved independence from Belgium in 1960, political instability has characterised much of its narrative. Since 1996, an ongoing conflict in the country’s eastern region is estimated to have killed six million Congolese people and displaced several million more. In the southeast region, a race for the country’s raw minerals only serves to complicate the crisis further.

At the heart of the matter remains a potent quagmire of armed conflict involving both paramilitary and state-sanctioned violence, a natural resource race, and corporate and foreign intervention by the Congo’s African neighbours – namely Rwanda but also Uganda, Angola, Zimbabwe and even Morocco – and international powers from further afield, including Belgium, Russia and Israel as well as the UAE, UK and US. In recent years, these factors have gone on to impact countless Congolese civilians both directly and indirectly in a daily, deadly crossfire of targeted and indiscriminate killings, modern slavery, sexual violence, mass displacement and land dispossession.

The situation in the Congo is thus extremely complex. Untethered to a sole push or pull factor, its roots are plural and multi-pronged, steeped in equal parts historical legacy and present-day economic and sociopolitical insecurity. These roots often lay imperceptibly beneath the surface, obfuscating the world’s attention and making a critical examination of what’s happening in the region harder to ascertain.

Want to support more storytelling like this? Become a Skin Deep member.

To quote the cultural theorist Stuart Hall, however, what’s happening is not a mere trick of the imagination. “It is not a mere phantasm either. It is something. It has its histories – and histories have their real, material and symbolic effects. The past continues to speak to us.” No longer does the past address us as simple, or factual. Instead, “it is always constructed through memory, fantasy, narrative and myth.” Hall’s words read almost as presciently as writings etched on the wall. Through them, we are reminded that the raging spectre of the Congo lives on; that its death-rattle may revisit us during a social media “doom scroll” when we least expect it, renting a chasm through our own reconstructions of time and space. Until we are able to confront the silencing of the Congo from our frames of consciousness – and the haunting of our collective memory this silencing begets – we will remain forever ill-equipped to take up arms in the fight to end its exploitation.

On 15 November 1884 in Berlin, 13 European nations – including Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain and Portugal – joined the United States to discuss the partitioning of Africa and the control of its natural resources. Taking place at a large horseshoe table overlooking the garden of German chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s yellow-brick residence on the Wilhelmstrasse, the conference lasted 104 days, including a short break for Christmas and the New Year. Referred to even at the time as the “Kongo-Konferenz” or “Congo Conference”, the 1884 Conference of Berlin would go on to embroil the Congo in a brutalising struggle for power and control of the region’s natural resources. In his closing speech to the delegates, Bismarck remarked: “The new Congo state is destined to be one of the most important executors of the work we intend to do.”

“Until we are able to confront the silencing of the Congo from our frames of consciousness – and the haunting of our collective memory this silencing begets – we will remain forever ill-equipped to take up arms in the fight to end its exploitation”

The quest for control of the Congo set the stage for the genocidal horrors that later took place under King Leopold II’s brutalising regime. The “rubber boom” of the perversely named Congo Free State would end in 1908, along with Leopold’s absolute rule, but not before an estimated 10 million civilian deaths due to the atrocities committed during Belgium’s 52-year colonisation of the region. Such an immense loss of life, so unimaginably large-scale, would remain indelible in the national psyche of the Congolese people for generations to come.

Spectrality could not be a more pertinent theme in our present-day analyses of what is taking place in the DRC. There are the spectral figures of history, the literal “ghosts” that stalk Belgium’s bloodstained colonial past – from Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected prime minister of Congo, executed in a CIA-backed coup, to the murderous Leopold. Then, there are the figurative revenants that return to us by way of the cultural canon. Stalking the pages of the literature we read, hiding in plain sight across our film and TV screens, these restless haunts speak back to us from the margins and from beyond the fourth wall, calling for our renewed attention on the Congo.

One such example is Spectres, a 2011 documentary by Sven Augustijnen in which, 50 years after Lumumba’s assassination, the spirit of the late prime minister returns to haunt the Belgian narrative of decolonisation. Illuminating the murky circumstances surrounding Lumumba’s tragic death, the documentary slowly unpicks the seams separating fact from fiction, lies from truth and appearance from reality, revealing a complex web of local, regional and international perpetrators in the demise of the nation’s revolutionary figure.

“Time and time again, we return to the Congo. The heart of Africa. The centre of the world as we know it. Before cobalt, there was copper. After rubber came gold.”

Time and time again, we return to the Congo. The heart of Africa. The centre of the world as we know it. Before cobalt, there was copper. After rubber came gold. Being at the axis of global demand is sadly nothing new in this part of the world. Today, we see the scramble for natural resources in the region simply take a new form. As modern-day consumers long-intertwined in these sprawling legacies of capitalism, consumerism, climate injustice and cobalt in the Congo, we straddle social and political borderlands bearing the strange fruit of the Congolese people’s labour by virtue of the lives we lead. With each new upgrade of smartphone, with every new Apple or Samsung product purchased, we cross and recross “una herida abierta” (an open sore), in the words of Chicana activist Gloria Anzaldúa, “where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds”.

The genocide in the Congo is far from silent. In recent months, it has raged louder still on our timelines and news feeds, with developments and information being reported in real time from the grassroots organisations and collectives on the ground – from Friends of the Congo to Goma Actif. Campaigner Mimie Wite-Nkate, who spearheads the Congolese Action Youth Platform (CAYP), is one such activist I engaged via social media. “We started in 2012 as a group of London-based Congolese activists from different organisations who wanted to have one voice to talk about the issues that the DRC was facing,” she says. “Through education and activism, we in the diaspora have already begun to shape history in a better way for the generations of young Congolese and African people.”

Wite-Nkate started a Goma Appeal fundraiser to support families living in camps in eastern Congo. Together with her team, she founded a global awareness campaign called Geno-Cost that has since evolved into a leading worldwide movement commemorating the victims lost to the country’s long history of violence. Bridging the possibilities of what true collective solidarity can look like from London to Lubumbashi, Gaza to Khartoum, Kinsasha and beyond, CAYP (and many more like it) offers a unique and unifying voice advocating for positive and peaceful change for communities affected by the genocide in the DRC. Wite-Nkate observes: “The diaspora plays an important role. These children of Africa are close to those who influence decisions in the motherland. Those influencers can also unfortunately double up as the new imperialists. How do we rectify this?”

Firstly, we who stand with the Congo must force ourselves to reckon with the consumerist behaviours and cultures we uphold. We can start by buying less, by only buying a new device when absolutely necessary – or even better, opting for second-hand as a first option. We can continue to advocate for change at policy level: writing to our local MPs and applying pressure on the governments to whom we pay taxes, who continue to fuel instability and fund violence in the region through backdoor aid deals with countries like Rwanda.

“We must force ourselves to reckon with the consumerist behaviours and cultures we uphold. We can start by buying less, by only buying a new device when absolutely necessary – or even better, opting for second-hand as a first option.”

Holding corporate entities accountable also yields results. With the added pressure of boycotting campaigns, we can advocate for greater transparency around ethical and sustainable supply chains that employ regulated, industrial extraction routes rather than deregulated, artisanal mining methods, all too often sourced harmfully through disparate armed groups.

Perhaps most important for us all is to continue amplifying and uplifting the voices of Congolese activists, groups and communities – through donations, digital engagement and voluntary support that continually builds on their praxis, efforts and livelihoods in tangible and transformative ways.

Stay in touch. Subscribe to Skin Deep’s monthly newsletter.