On 7 October 2023, video footage circulated on social media of a bulldozer breaking down an Israeli-built fence around Gaza.

This use of a bulldozer by Palestinians against Israeli infrastructure was a reversal; for decades, JCB and Caterpillar bulldozers have been instrumental in Israel’s systematic demolition of Palestinian homes and built space, and continue to be used in the ongoing ethnic cleansing in Gaza. The same bulldozers are used in India and Kashmir, where the Hindu nationalist government of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has targeted homes and workplaces of the Muslim population.

The politics of this piece of construction equipment and its long use by regimes of oppression provided the theme for a recent issue of The Funambulist, a magazine that explores, in the words of editor-in-chief Léopold Lambert, “various political struggles in the world, including anti-colonial, anti-racist, queer and feminist struggles… through a spatial perspective, often looking at geography, cities, the built environment, objects and clothing.” Skin Deep spoke with Léopold, The Funambulist’s editor-in-chief, and Shivangi Mariam Raj, the magazine’s head of communications and contributor to its November-December issue “Bulldozer Politics”, which takes on architectures of ruin, rubble as testimony, and how bulldozers require us to rethink what counts as a weapon.

Skin Deep: What is The Funambulist?

Léopold Lambert: The Funambulist was originally a blog, which I created in 2010. Back then, I was still an architect – I don’t know if I count as one anymore. I was mostly writing about architecture’s complicity with various regimes of oppression – in particular, settler colonialism and Palestine. In 2013, I started a podcast to operate alongside the blog, and a couple of years later, the magazine started.

Our editorial objectives are to approach various political struggles in the world, including anti-colonial, anti-racist, queer and feminist struggles. We read them through a spatial perspective, often looking at geography, cities, the built environment, objects and clothing. We also try to cultivate internationalist solidarities between these various political struggles.

Skin Deep: Why centre this issue on bulldozers?

Léopold Lambert: The theme mostly emerges from a book that I wrote (in French) shortly after the last murderous siege on Gaza in 2014. Back then, it seemed like the worst we were going to ever see.

It struck me that, in the Israeli army’s various bombings, and in the broader Zionist project, there was a methodical order to the destruction at play. This was a contradiction – between the chaos of rubble and the very specific political order behind what was producing that rubble. My book tried to articulate this order, enacted by the bulldozer, tracing its use all the way back to the Nakba of 1948. My argument is that the order of destruction is quite similar to the order of construction contained in an architecture project. In the case of settler colonialism, the destruction of Palestinian homes and the construction of settler infrastructure go hand in hand.

Shivangi Mariam Raj: In the context of the Subcontinent, various grades of spatial injury are inflicted on the minoritised and colonised communities in order to precipitate their political erasure. Violence is usually understood through hypervisible images of blood, and of bodies in suffering. But rubble carries a very specific kind of violence — a violence without blood — which is simultaneously performed in public space and also concealed and hidden in that very space.

I like to think of the term “architecture of ruin” to understand how rubble creates a certain kind of a landscape. For example, in India, there is a massive project of Hindu Rashtra being choreographed by the Hindu supremacist forces. Hindu Rashtra refers to the design of “greater, undivided India,” whose expansionist ambitions are driven by collapsing the sovereignty of all neighbouring nations of the Subcontinent and folding them into Hindu monoculture. Right now, we are seeing this Hindu Rashtra emerge through the very calculated and targeted ruination of Muslim spaces in India as well as in Indian-Occupied Kashmir. This is how the project of Hindu Rashtra becomes materially tangible: through this object of rubble.

We won’t have the tools to resist the order that rubble has been assembling in space until we are able to name and identify the anatomy of this violence, which has been quite cleverly rearranging the built environment. With bulldozers, there is a precise demographic engineering under way, dictating which populations are allowed to survive, how, how much, and where. It’s an instrument of population management, which is heavily dominated by the logic of caste.

“This was a contradiction – between the chaos of rubble and the very specific political order behind what was producing that rubble.”

SD: What is the “architecture of ruin”?

LL: The phrase “architecture of ruin” was coined by Shivangi Mariam. The term that I use, somewhat in the same family, is “ruination”.

In Palestine, this process of ruination is particular in the way it has been calibrated. Colonial states generally have no problem leaving ruins behind in the process of ethnically cleansing indigenous populations. But, in the case of Palestine, there is a double destruction. There is a destruction of the homes themselves, but then, there is also a destruction of the ruins, the destruction of the evidence of that ethnic cleansing. This is necessary to make the settler colony align with the famous Zionist slogan: “a land without people, for a people without a land”. And so this destruction, not just of the homes but of the ruins themselves, is done specifically for this narrative to become a reality, or at least a sort of fantasy of a reality on the ground.

SD: If we think of bulldozers at all, we likely think of them as neutral, or even benign, objects. Are we wrong to do so?

SMR: You might assume that a bulldozer cannot be a weapon because it is a piece of construction equipment, or it is an equipment that rescues people from natural disasters such as landslides, floods, and earthquakes. However, this is exactly how companies like JCB are able to make a profit out of their machinery being used for these forces of political domination. It’s an object that is hard to suspect because of its ordinariness, its performance of innocence. In his work, Léopold has compared the bulldozer to a bomb, and I find that bulldozer’s violence is even more dangerous precisely because we are not able to recognise it as such.

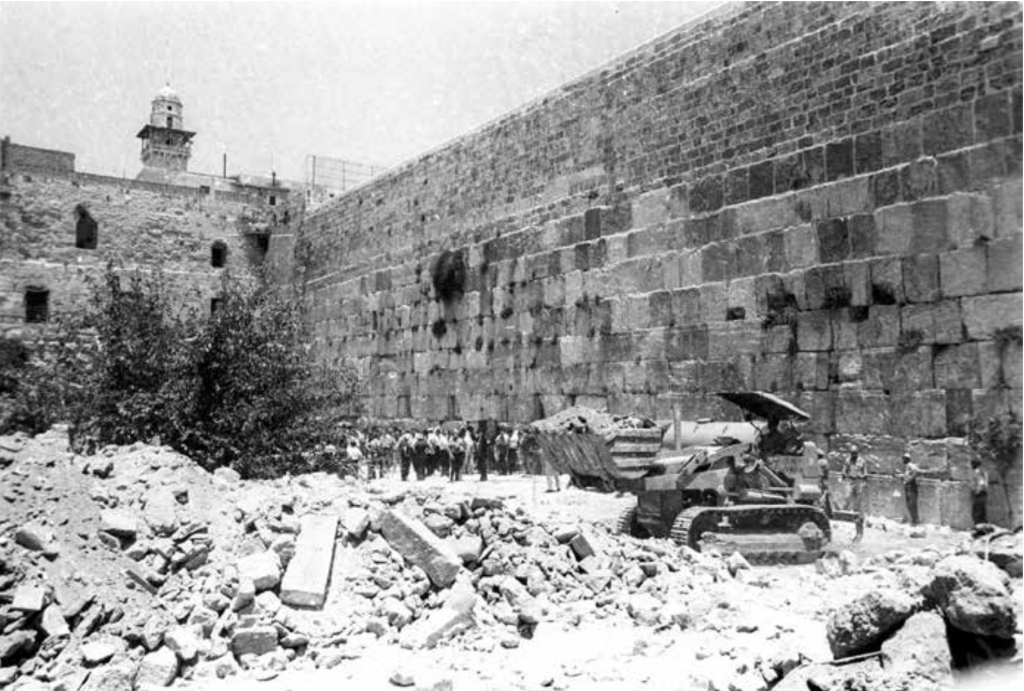

LL: In the case of Palestine, the bulldozers of 1948 or even of the bulldozers that destroyed the entire al-Maghariba Palestinian neighborhood in the old city of Jerusalem, were very much in line with the sort of bulldozers we think about today. They have been refined and customised in close collaboration with the US company Caterpillar, which is on the [priority target] list of the BDS campaign.

SD: You’ve spoken about the presence of bulldozer symbolism and imagery in the mainstream – for example, bulldozer toys for children, or images of rubble circulated widely on social media. What’s the impact of this?

SMR: I think, first of all, it creates a way for the majoritarian and the settler identity to consolidate itself, and articulate itself. It also becomes a way to somewhat soothe the anxiety that is inherent to nation-state projects, whether it’s the Israeli state or the Indian state.

Whether it is the ruination in Palestine or the ruination in Kashmir or of the Muslim homes in India, there’s a concerted effort all across social media to multiply images of rubble. We keep on circulating these images in the hope to create awareness or to document evidence. But right now, the settlers, the soldiers, the perpetrators themselves are creating and distributing images of their own crimes. So, how are we supposed to look at this rubble? We do not know if these photographs are being produced because of this debris or more debris is being deliberately produced for these photographs. This economy of image production follows, once again, the logic of spatial domination, freezing the body and time of the minoritised and the colonised in a site of perpetual ruination.

I also use this term “weaponisation of archaeology” to describe how mosques in India are being dug and demolished in search of some imaginary “glorious Hindu” past, or in Palestine, where digging and destruction of entire neighbourhoods is justified as an assertion of a biblical past. Archaeology carries this objective, neutral, scientific face, and our oppressors weaponise this to fabricate national mythologies.

Want to support more storytelling like this? Become a Skin Deep member.

SD: How do images of rubble interact with time and temporality?

SMR: I think rubble is a testimony of the object that preceded it. It’s like looking at the same object, but in a gaseous or vaporised form. But it’s still the same thing. And to still view it like that, you need an ethic of absence, of honouring the disintegrated space, of honouring this kind of loss, because it’s monumental. It’s impossible to stand in any of the Muslim localities in India today and not breathe the dust that is coming out of somebody’s broken home. In Kashmir, thousands of Muslim homes have been destroyed so far as a celebrated “counterinsurgency tactic”.

And we cannot even begin to mourn this loss without holding on to an ethic of absence. For example, the 12th-century grave of Baba Haji Rozbih – which is said to be the first Sufi shrine ever in Delhi – was demolished by a bulldozer. But the khadim, the person who takes care of the shrine, still rearranges the stones, and maintains his act of worship with incense and roses. There are also caste-oppressed Muslim families in Nai Basti, Mathura, whose homes have been demolished, and they don’t have anywhere else to go. But they declare, “we will live inside this rubble”. Or how Palestinians in Gaza say, “ahna samidoun hon” (we will stay here). This idea of waiting with something that is absent, something that doesn’t exist, so to speak. The vocabulary of absence helps us grapple with this colossal loss.

SD: Are there examples of resistance to, or subversion of, bulldozer politics?

LL: The use of the bulldozer by Palestinians in Gaza on October 7, 2023, was a spectacular example. That incredible photo of that bulldozer opening the door of the prison, so to speak, dismantling the sort of siege wall surrounding Gaza and opening a way out. I’m pretty sure in my life, I’ve seen a few uses of the bulldozer itself in opposition to what we’ve been describing for the past hour, but this is surely the most spectacularly resistive one. The destruction of that architectural apparatus that I’ve been describing many times in my work hit home quite simply.

SMR: The tunnels dug across Palestine are a stunning example of reclaiming space. They are an abolitionist form of architecture.

The production of debris is a bordering practice, but tunnels abolish these borders, allowing families and loved ones to cross Zionist fictions in space and circulate food, exchange greetings, and organise an infrastructure of resistance. [Another example] is when armoured bulldozers are destroyed by the Palestinian resistance, they’re then repurposed and used to make weapons.

We also have examples in India where Muslims in a particular neighbourhood burnt the bulldozers down and prevented the demolition of their homes. There’s a refusal, reversal, and a certain kind of reclamation that is practiced within these spaces; the same space that generates so much violence also becomes a space to stay put, to refuse to move, to reject being consumed by this logic. A major part of bulldozer violence is to constrain and constrict us, to choke our bodies and our atmosphere with so much dust that we can’t even breathe, and so we can’t even begin to comprehend what’s happening to us, we cannot even begin to grieve.

Muslims in Kashmir use the term “martyr” for homes and mosques that have been demolished. I find this to be an idea filled with so much dignity: it signals towards the fact that the loss of a home is not just brick, mortar, concrete, stone, and iron, but also intergenerational histories and memories.

While they are trying to manufacture a certain history over our bodies, we are creating and preserving our own memories, which are at the forefront of the resistance. Our memories will outlive their mythologised projects and their empires of dust.

Stay in touch. Subscribe to Skin Deep’s monthly newsletter.